Ayouba Swaray ’24

Contributing Writer

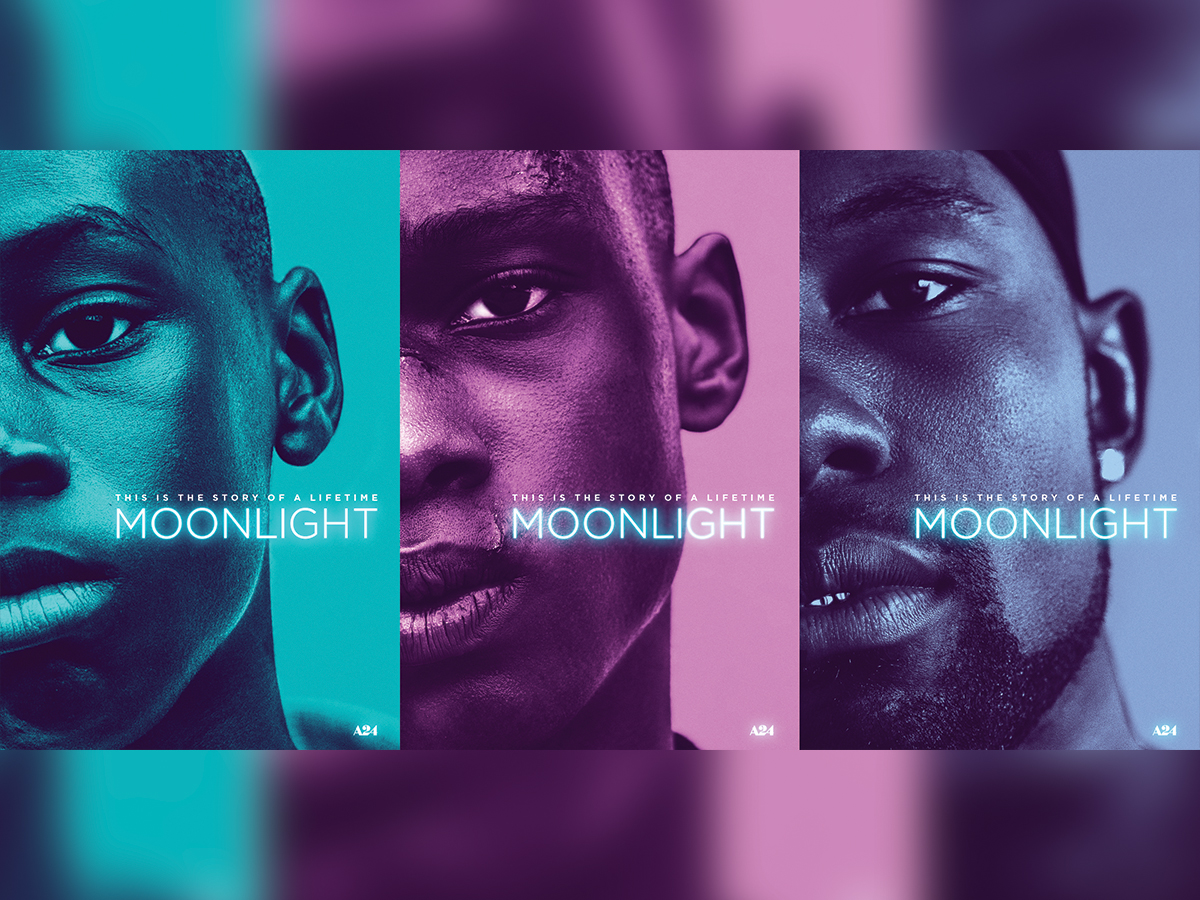

The conversation surrounding queer coming-of-age films in the modern canon is most often stimulated by the fantastical projections of a dynamic interrogatively yearned for as in Call Me By Your Name or Brokeback Mountain, or the navigation of queerness and identity within a robustly heteronormative arena as seen in Booksmart and Alex Lovestrange. Despite the multifariousness in the delivery and ethos of these films, the commonality they all maintain is the paradigm in which they engage queerness within the confines of heteronormativity: whiteness. It wasn’t until September 2nd, 2016, that a film in this canon truly began to peel back the layers queerness finds itself influencing and how it looks from an intersectional, not so picturesque perspective. This date marks the release of Barry Jenkins’ Academy Award-winning film Moonlight. Originally written by Terrell Alvin McCraney, the film follows protagonist Chiron through three critical stages of his life as he grapples with masculinity, love, and his deeply repressed queerness in the impoverished, gang-riddled, drug capital landscape of Liberty City, Miami. Unlike other films, Chiron’s queerness wasn’t neatly objectified nor did it have recognizable enough plights to make his experience familiar enough to digest. His queerness was informed by the intersectionalities of his identity, and the film beautifully depicted the performance he had to maintain in spite of his queerness, resulting in him never truly learning how to receive or give love as an adult. It was my first time watching the turmoils of queerness being explored not within the palatable boundaries of white queerness, but in something much more profound, more real. In order to effectively capture the differences in approach, I’ve compared the thematic elements and mechanisms of Moonlight to the film I regard as the paragon of white queer films and Moonlight’s antithesis: Love, Simon.

Love, Simon follows a closested queer boy trying to figure out the identity of an anonymous fellow queer he’s fallen for while trying to juggle the trials and tribulations family, friends, and high school throw his way. Of all the adjectives that were used to describe this movie and the grounds for its success, the one that triumphed over all was its “relatability.” Simon is a caucasian, middle class suburbanite with a white picket fence family and a lively group of friends. The role queerness had within his character and the film was palpably one dimensional, a plot device used to assert his difference and draw from a self-evident source of conflict. The reasons for its purported relatability was because queerness in the film was packaged through a heteronormative archetype, which was informed by the inextricable underscoring of heteronormativity in white queerness. This isn’t to say that the experience depicted in the film wasn’t valid, but that the “relatability” of the film all but confirms the kind of audience the film catered to and the extent to which they chose to stretch the expanse of queerness in a lived identity. Here we have the model queer coming-of-age story that’s fun for the family with which anyone can relate to—anyone but queer people, that is. This is in stark contrast to Chiron, who slumbers in the projects of Vice City with his crack-addicted mother, eventually becoming a drug dealer himself through the systematically predestined influence of his environment and peers. Queerness in this film is characterized by its contained fluidity: tumultuous, inconspicuous, freeing, convoluted, but above all, always questioning. It need not announce itself as it already looms over every scene. Every decision Chiron chooses to or not to make is interrogated by his queerness as it isn’t an identity marker he can define so easily such as his Blackness or his poverty. The struggle we see is one where Chiron couldn’t make sense of this inexorable phenomenon that challenged everything he knew about himself and his place in society. He wasn’t resourced with the cultural liberalisms of suburbia, didn’t have the financially and emotionally supportive mom and dad who’d love him unconditionally, and wasn’t gifted with peers who accepted him with open arms with whom he could even divulge this monumental anchor he carried. Moonlight presents queerness within conditions that don’t source its truth from a proximal universal “relatability,” but frames queerness as a living, ineluctable facet of one’s being, unfailingly challenging the understanding of self and shaping it in turn.

Moonlight’s gritty portrayal of the tightroping Black men must choreograph when piecing queerness into their understanding of self in a modern day America certainly marks a thematic departure from the rest of its cohort in the queer coming-of-age film canon. The film, however, redefined how queerness can look and feel onscreen, and while it doesn’t have a fairytale ending, it leaves viewers with questions that’ll forever reorient their understanding of queerness and its elusive properties.

[…] Source […]