Donald M. Bishop ’67

Alum Contributor

Millions of combatants were locked in sanguinary combat on the Western Front when the U.S. entered World War I on April 6, 1917. The population of the U.S. was 103 million people, but the strength of the U.S. Army was a pitiful 127,500 men.

When the war ended 18 months later, the Army was more than 4.1 million soldiers strong. The Navy had 194,000 sailors in 1917, only to grow to more than half a million in 1918. These raw numbers are impressive, but there was much more to the prodigious mobilization. And Trinity’s alumni were part of it.

After Congress passed the Selective Service Act – the draft – on May 18, 1917, millions of eligible men were registered and examined. Millions of new soldiers and sailors needed millions of uniforms and weapons and thousands of trucks.

When they were civilians, the new soldiers had taken care of their own meals and lodging, but they now had to be fed in “chow halls” and housed in barracks, which had to be built. Sleepy Army and National Guard camps expanded. New camps with hospitals, chapels, roads, stables, training grounds and ranges were constructed. Automobiles were still rare, so many soldiers who were to be drivers had to be taught to drive.

Canners and meat packers prepared tens of millions of rations for the camps and the front – often consumed as stew or hash, “slum” in Doughboy lingo. Farmers grew more crops and raised more animals. The nation’s railroads groaned as they moved men, horses, material, weapons and food.

After weeks of basic training, new soldiers had to be assigned to branches (infantry, artillery, ordnance, medical, quartermaster, signals, air service, etc.) and receive specialized training. They were formed in platoons, companies, regiments, brigades and divisions, and trained some more as units.

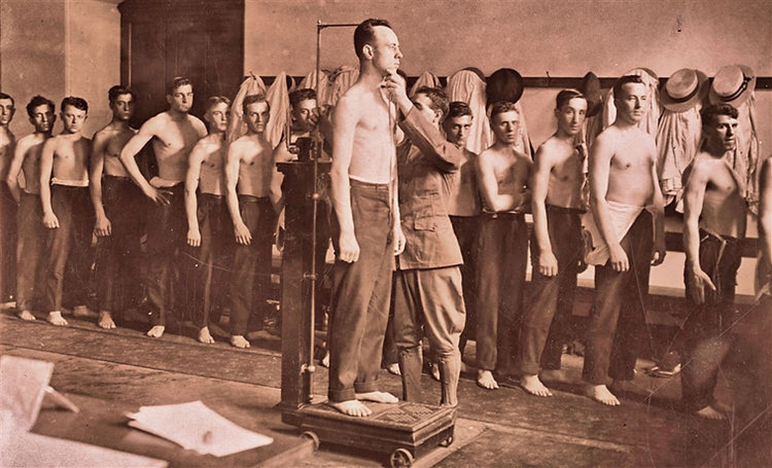

Each of the millions of men eligible for the World War I draft required a medical examination. Dr. Victor Cox Pederson, Class of 1893, was commissioned in the Army’s Medical Reserve Corps. Major Pederson worked in New York City as a consulting physician to the Selective Service headquarters, recognized for his expertise in urology and venereology.

After graduating from Trinity, Lloyd William Clarke ’07 became an instructor at then-popular military secondary schools. It was valuable experience, and he was commissioned in the Officers Reserve Corps the month before the U.S. declared war. The Army assigned him to train officers at camps in Texas and Arkansas, and until he was struck down by influenza and pneumonia on Oct. 23, 1918, Major Clarke commanded a battalion of officer candidates at the Central Officers Training School at Fort Pike in Little Rock.

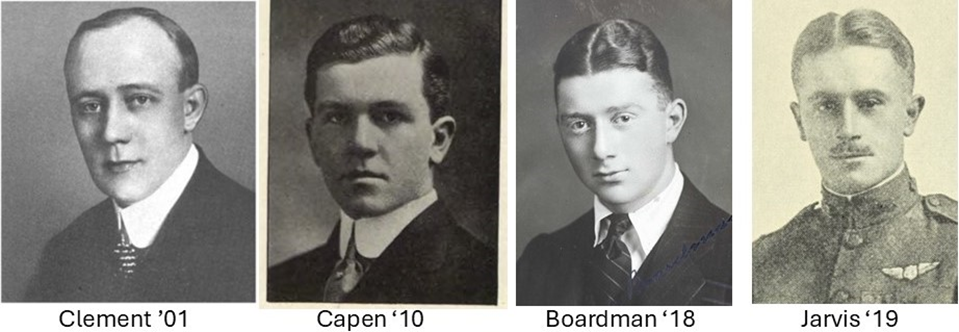

George Cleveland Capen ’10 left his insurance career at The Travelers for the war. In 1917, he trained at Plattsburg and was commissioned in the field artillery. He remained in Plattsburg for two years as an artillery instructor.

Samuel Gardiner Jarvis ’19 did not wait to graduate with his class at Trinity. He enlisted after President Wilson asked Congress to declare war. After short stints in Hartford’s Troop B in the Connecticut National Guard and in the Ambulance Corps, he trained at the aviation ground school at MIT and earned pilot’s wings in Louisiana. He trained new airmen in aerial gunnery, combat flying and armaments.

In 1917, Thomas Bradford Boardman ’18 spent six months in France as a Red Cross ambulance driver. Commissioned in the Army’s field artillery, he joined operations in the Chateau-Thierry area in the spring of 1918. So great was the need for Army schools to benefit from experiences at the front that he was returned to the U.S. to be an instructor at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and other posts. Unfortunately, he died of influenza and pneumonia on Oct. 23, 1918 in Kentucky.

After leaving Trinity, Martin Clement ’01 was a fast rising star in railroading, and he would later be President of the Pennsylvania Railroad. When President Wilson nationalized the railroads in the name of efficiency for the duration of the war, he became an advisor to the U.S. Railway Administration.

After graduation, the career of William Bowie ’93 was with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. The immediate need for detailed, constantly updated maps from along the front made mapping a large enterprise in France, and Major Bowie was a man of the hour at the Washington end.

Weapons produced for the Army by Remington, Colt, Browning and other firms had to pass quality inspections. As a lieutenant in the Ordnance Reserve Corps, Frederick William Lycett ’06 spent most of the war in the Colt factory in Hartford. Colt manufactured 425,000 automatic pistols during the war.

For evaluation, research, development and proof-testing such weapons as artillery, mortars and ammunition, Uncle Sam acquired 55,000 acres of land and water in Maryland, establishing the Aberdeen Proving Ground. First Lieutenant Raymond Conklin Abbey ‘10 spent the war at the new “home of ordnance.”

Dewitt Clinton Pond ‘08 went on to study architecture at Columbia, and he wrote a basic textbook: “Engineering for Architects.” During the war he worked for the Naval Inspection Service of the Bureau of Engineering, which inspected ships, aircraft and machinery.

In his teens, Clarence Denton Tuska ’19 was fascinated by crystal sets, and his interest matured into full-time focus on wireless telegraphy. At age 17 he was a co-founder of the American Radio Relay League. Commissioned in the Army’s Signal Corps, First Lieutenant Tuska established the Air Service’s radio training school at Ellington Field, Texas.

When poison gases became weapons on the Western Front, the U.S. Bureau of Mines was tasked to study their properties and develop countermeasures. After graduating from Trinity, Henry Gray Barbour ’06 received an M.D. from Johns Hopkins. For the Bureau, he was among the Yale Medical School faculty who studied gases, especially chlorine.

Part of mobilization was sustaining popular support for the war effort. When wartime theatergoers watched films, it took about four minutes to load the next reel of a feature. The Wilson administration’s Committee on Public Information organized “Four Minute Men” to give speeches during the empty time. In North Carolina, Rev. Isaac W. Hughes ’91 was one.

Trinity men – in uniform or civvies – played many roles in this vast mobilization, and many proved so valuable that they remained in the U.S. Their part in the war was amobilization for the war.

This article is the fourth part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part three, click here. For part five, click here.

+ There are no comments

Add yours