Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

In 1917, hundreds of Trinity alumni joined the armed forces to fight in the Great War, and many students left the College. They enlisted, trained, joined units, sailed in convoys through the U-boats and eventually reached France.

More months of instruction by French and British trainers and advisors followed. These Europeans were alarmed by American boastfulness, naivete, and overconfident eagerness to whip the Germans. The Allied high command was also dismayed when they learned of General Pershing’s belief in the decisive power of the rifle and bayonet; too many of their own riflemen had been slaughtered by machine guns and artillery barrages.

Usually, then, the American troops were first deployed to a “quiet sector” to learn the ropes of trench warfare and to gain experience. Sometimes, however, those sectors proved not so quiet, and the German offensives in 1918 bloodied the first American units that joined the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). This article speaks of Trinity alumni in the leading cohorts.

National Guard

Many alumni reached France early because they were already trained and organized in National Guard units. The 101st Machine Gun Battalion and the 26th “Yankee” Infantry Division (discussed in part two of this series) included dozens of Trinity men.

Glastonbury clerk William W. “Bill” Buck ’11 joined the Connecticut National Guard and served on the Mexican border. In France, Sergeant Buck was first a supply sergeant and then returned to the fighting line—at Chemin des Dames, Toul and Chateau-Thierry. He absorbed a shell wound on July 25, and he was invalided home before 1918 ended.

Captain William Spaulding Eaton ’10, a Hilltopper on the gridiron and diamond, was another veteran of the Mexican border. When war came, he was soon commissioned and fought in Yankee Division’s early engagements. In August 1918, he returned to the U.S. to be an instructor.

Michael Augustine Connor ’09 joined the Connecticut National Guard in 1907 and deployed to the Mexican border as a lieutenant. After being promoted to Captain, he commanded the Supply Company of the celebrated 102nd Infantry Regiment.

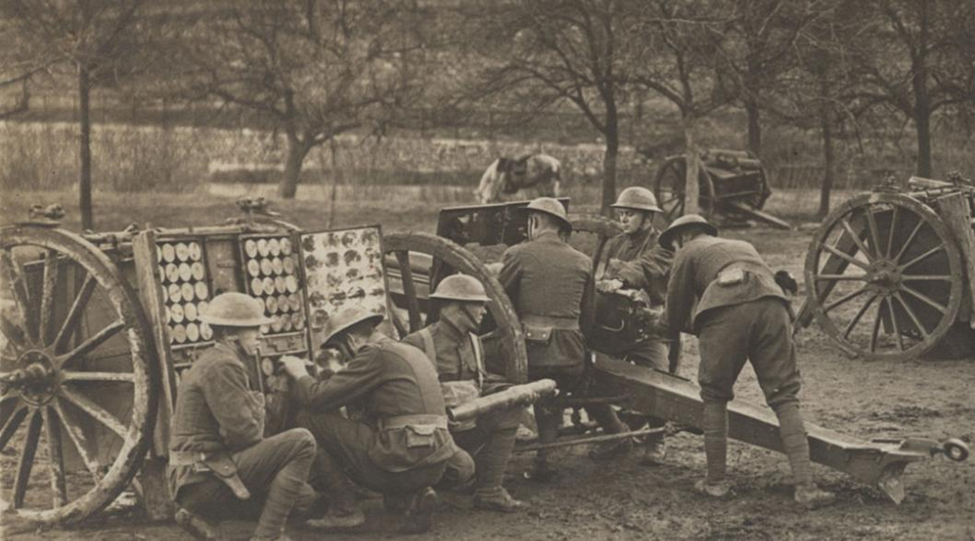

Captain James Kirkland Edsall ’09 of the Minnesota National Guard had also been called up for the Mexican border. In 1917, his Guard unit became the 151st Field Artillery, part of the 42nd “Rainbow” Infantry Division (Douglas MacArthur was Assistant Division Commander). The 151st was in near-continuous combat for four months.

Second Lieutenant Harry H. Denning ’17 reached France in the 125th Infantry Regiment of the 32nd “Red Arrow” Infantry Division, formed from Michigan and Wisconsin units of the National Guard. In the Second Battle of the Marne on July 31, 1918, a French general who observed the Division’s attack called them “Les Terribles,” and the name stuck as it repeatedly advanced. Alas, Denning was severely wounded by sniper fire that same day.

More Early Arrivals

Parker Van Amee ’07 had been ordained in the Episcopal Church. Rather than become a chaplain, he trained at Plattsburg, became an infantry officer, reached France and was wounded in a German bombing raid. Fighting in Chateau-Thierry, command of the Machine Gun Company of the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the 2nd “Indianhead” Infantry Division devolved on him. He later led the company at St. Mihiel. He succumbed to wounds and pneumonia on Oct. 2, 1918. He is buried at the Suresnes American Cemetery in France.

Second Lieutenant Horace Richardson Bassford ’10 was originally assigned to the Coast Artillery Corps defending Long Island Sound. His 56th Coast Artillery arrived in France in August 1918 and first fired its 155mm guns in the Oise-Aisne offensive. He would later fight in the Argonne.

Archibald Morrison Langford ’97 had been captain of Trinity’s football team; he joined the Army twenty years later. His 1st Regiment of Pioneer Infantry, trained as infantry and combat engineers, repaired and built roads and bridges as the AEF fought in the Aisne-Marne, Oise-Aisne and Meuse-Argonne campaigns.

William Beach Olmsted Jr. ‘16 and his brother, Frederick Nelson Olmsted ‘19, drove ambulances in France for the American Field Service for four months in 1917. William was then commissioned in the U.S. Army Motor Transport Corps, attached to the French Army Reserve Mallet (long-distance trucking) for artillery transportation. He served until the armistice through seven campaigns.

The AEF depended on horses, and the U.S. sent a million animals to France. They were received, moved, cared for and distributed to the front by the Quartermaster Corps. First Lieutenant Chester Dudley Ward ’13 served in the 326th Field Remount Squadron at Carbon-Blanc, Gironde, France.

Trinity’s Marines

Two Marine Corps regiments reached France in 1917, becoming the Fourth Marine Brigade in the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division. Although the Marines also fought in the final offensives and joined the occupation of Germany, the most legendary fight of the “Devil Dogs” was at Belleau Wood in June 1918. Some 5,000 Marines were killed or wounded in a struggle that lasted three weeks.

William Washington Brinkman ’15 had served as a U.S. Vice Consul in Coburg and Hamburg just before the U.S. declared war. Exchanged, he joined the Marine Corps as an infantry lieutenant. In the 5th Marine Regiment, he fought at Belleau Wood – and later at Soissons, St. Mihiel, Mont Blanc Ridge, and the Meuse-Argonne. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre.

Corporal William Lawrence Peck ’17 served in the 6th Machine Gun Battalion of the 6th Marine Regiment at Belleau Wood and later battles, receiving a Citation Star and the Croix de Guerre.

Harold Colthurst Mills ’15 was an Army infantry lieutenant sent over to the Sixth Marines at Belleau Wood. He was wounded on June 10, 1918, the fourth day of the battle, died a week later and was buried at the Aisne-Marne American cemetery. He hoped to become a missionary in Alaska.

The II Corps and the Hindenburg Line

Arriving in France in 1917, General Pershing faced enormous pressures to send his arriving formations to strengthen the French and British lines with fresh Americans. His goal, however, was to take command of a fully American sector of the front line, assemble a large American army in Lorraine and attack.

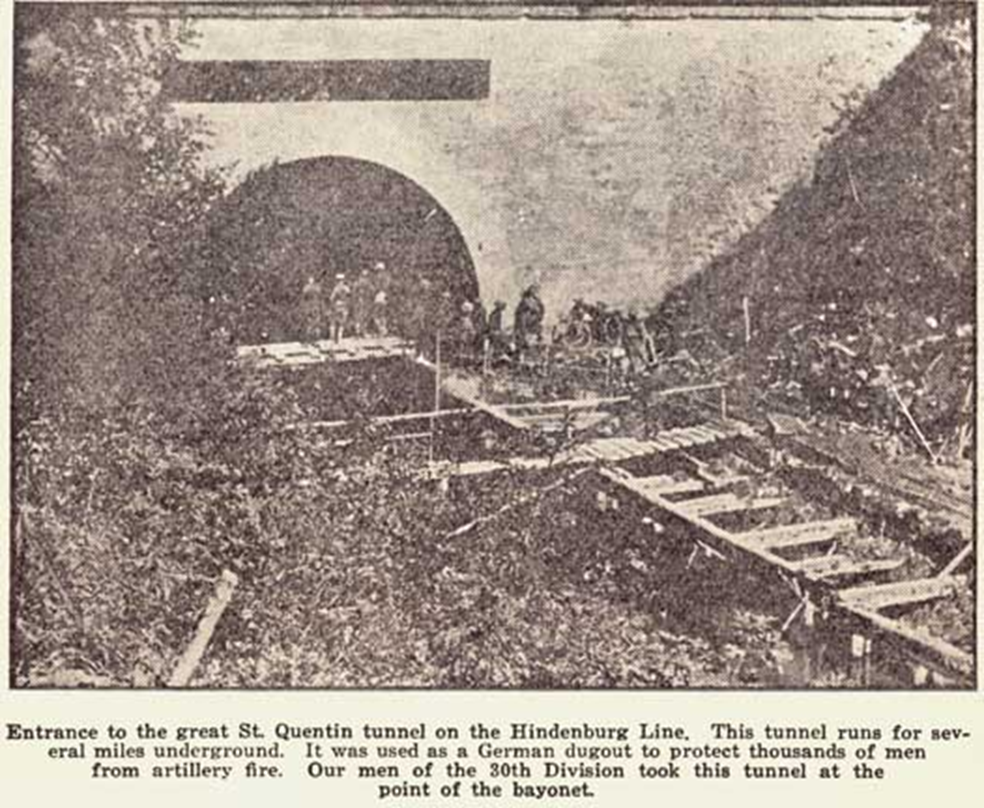

In time, though, he partially yielded to the pressures. He sent the two African American divisions to the French and two National Guard divisions to the British north of Paris. The two latter divisions – the 27th (New York) and the 30th (Tennessee and the Carolinas) became the II Corps. Eventually the two fought with the Australian Corps. Their day of glory was Sept. 29, 1918, assaulting the prepared German defenses of the Hindenburg Line.

A journalist and a teacher after graduation, Second Lieutenant Henry B. Dillard, Jr. ‘13 was sent to the 30th Division in late 1917. His 105th Engineers marked lanes for the attack, cleared minefields and reconnoitered German positions for the Division’s storm at the St. Quentin Canal-Tunnel. Second Lieutenant Francis Earle Williams ’13 was an ordnance officer in the Division, supplying its firepower.

Two Trinity men—Captain Harry Woodford Hayward ’97 and Private James Jellis Page ’08—gave their lives in the 27th Division’s attack. Two veterans of the New York Guard’s deployment to the Mexican border were also there: Charles Richardson Whipple ’12 was in the 105th Infantry Regiment, and Private First Class Nathan Pierpont ‘16 joined the attack in the regiment’s Machine Gun Company.

These were some of the Trinity alumni who reached the front before the great American offensives in the autumn of 1918. Many more—in many different roles—would follow.

This article is the sixth part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part five, click here. Part seven will be released Dec. 22, 2024.

+ There are no comments

Add yours