Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

In 1917, American war planners—viewing the vast gap between the nation’s latent industrial, economic and financial power and the pitiful size of the U.S. Army and Navy—knew they must draw on civil society to rapidly expand the war effort. Two organizations were most prominent in their thinking.

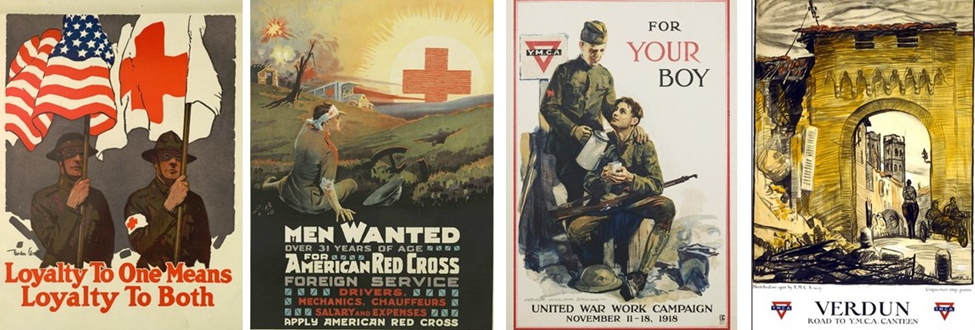

The American Red Cross

Military and civil leaders knew the medical demands of the war would be intimidating, and the American Red Cross (ARC) had provided medical services in emergencies, disasters and the war with Spain. When the Great War broke out in 1914, the ARC had sent the SS Red Cross, “the Mercy Ship,” to Europe with 170 surgeons and nurses, and by 1917 it had sent 340 more ships with medical supplies and staff, so it already had wartime experience.

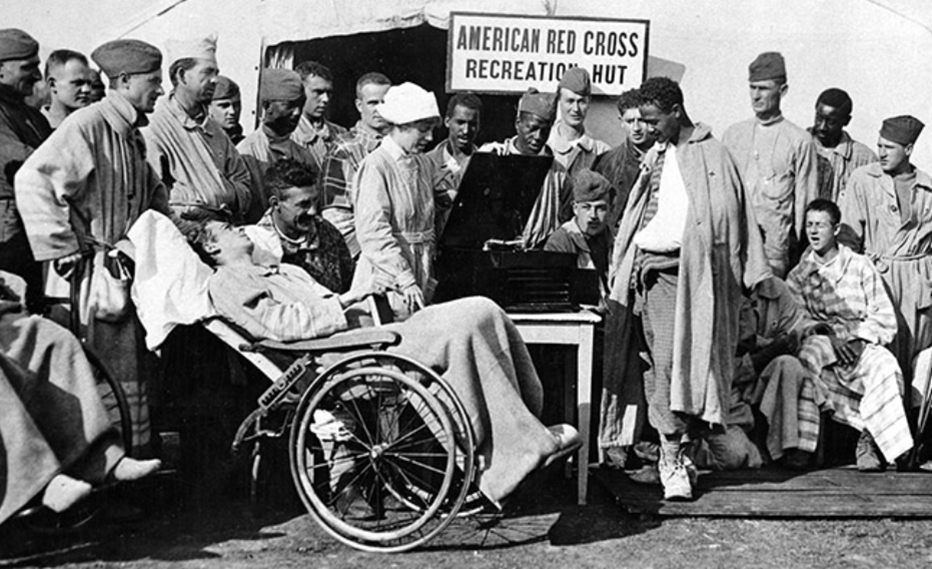

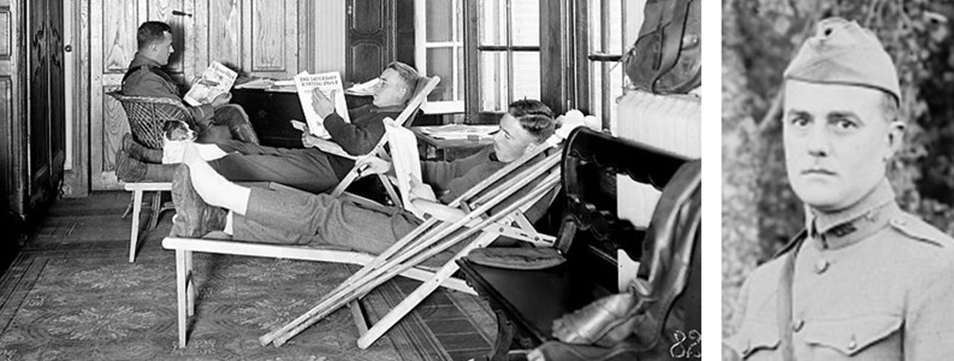

Beginning in May 1917, the Red Cross began sending full hospital organizations to Europe. It established 54 base hospitals, employed thousands of doctors, nurses and chaplains, organized ambulances and trucks, provided relief to refugees, and shipped food packages to POWs held by Germany. It provided “canteen services” to soldiers as well. At home, it expanded prodigiously and raised millions of dollars, helping mobilize the nation to provide war relief.

The Red Cross provided many Trinity alumni who were too old or otherwise disqualified for military service to join the war effort. More than half had graduated in the 19th century.

In 1917, for instance, the Army did not accept Dr. John Butler McCook ’90 because of hearing problems associated with his previous service in the war with Spain. He volunteered to serve under the American Red Cross without pay and arrived in Paris in September of 1917. Working first at the American Hospital in Paris, the ARC sent him to take charge of a hospital in Bretigny and then one in Arc-en-Barroise, treating wounded French soldiers.

(Photos accessed via the American National Red Cross photo collection, Library of Congress)

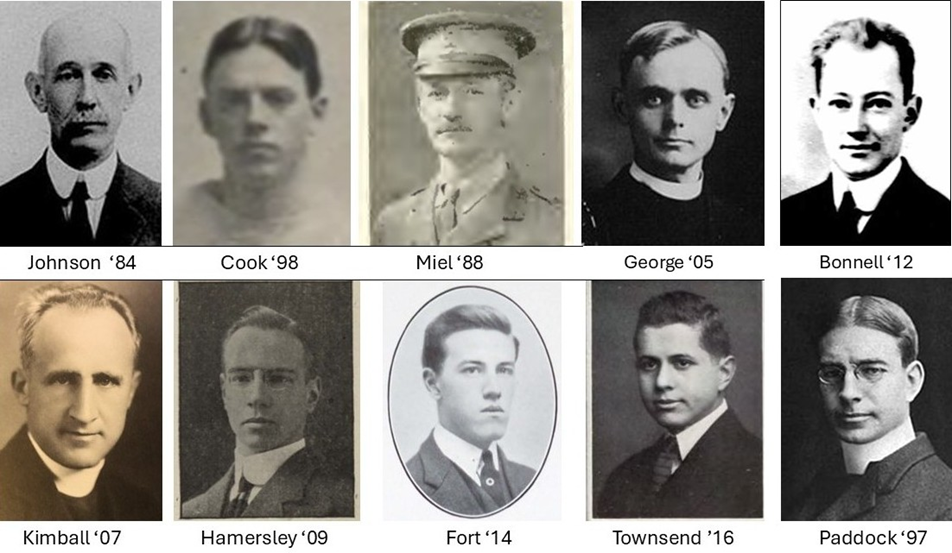

Ernest de Fremery Miel ’88, pastor of Trinity Church in Hartford, was 50 years old when the war began. He volunteered for the American Red Cross and reached France in early June 1917. In the next year and a half, he ministered to the U.S. Army’s 1st Division, served at the ARC headquarters in Paris and at two base hospitals, and became an ARC field chaplain, serving with the medical troops of the 26th “Yankee” Infantry Division. He made many visits to the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, allowing him to see his son Charles (Class of 1920) and other Trinity alumni.

Although he had served with the Connecticut National Guard on the Mexican border in 1916, weak eyesight disqualified William James Hamersly ’09 for more active duty, so he led Red Cross home service work in its Atlantic Division. At Camp Devens, Massachusetts, he contracted influenza and pneumonia and died on Oct. 12, 1918. That his name is carved on the wall of Trinity’s chapel shows that the College honored Red Cross personnel among those who gave their lives during the war.

John Hardenbrook Townsend ’16 had been a member of the Bible and Mission Study Committee of Trinity’s YMCA. Graduating in 1916, he directly volunteered to drive ambulances in France—first with the French and then the American Red Cross—moving wounded from the front lines to medical care.

Recently ordained in the Episcopal Church, Norman Captive Kimball ’07 was Assistant Director of the American Soldiers and Sailors Club in Paris.

And missing the leg amputated while he fought with the French Foreign Legion in Champagne in 1915, Brooke Bartlett Bonnell ’12 returned to France as a driver for the ARC.

The College’s Honor Rolls list at least 17 alumni who served in the ARC. This is likely an undercount since many ambulance drivers eventually served in the Army.

The Young Men’s Christian Association

Two million American soldiers reached France by the war’s end. It was the YMCA that provided support and “welfare”—rest and recreation programs for soldiers, sailors and marines, canteens and exchanges, overseas entertainment, troop education, and work with prisoners of war. At home and in Europe, the YMCA’s Red Triangle logo was highly visible.

The College’s Honor Rolls record 31 Trinity men who served with the YMCA during the war, 15 of them in France and three in the British Isles. Others served at Army posts in the U.S. where units were organized and trained, and a few managed the exploding number of Red Cross chapters and activities in the 48 states. Fifteen were Episcopalian clergy, including the Right Reverend Robert Lewis Paddock ‘04, the first Bishop of Eastern Oregon, who was sent to France. He was a “canteen hut general secretary.”

Two had interesting intercultural experiences. James Hardin George III ’05 had studied for the priesthood after graduation, and he taught at St. John’s University (founded by the Episcopalian Church) in Shanghai. Returning to the U.S., he volunteered for the YMCA, listing his languages as Chinese, Ethiopian, Sanskrit and Greek. He was sent to work with Chinese laborers, mostly from Shandong province, recruited by the British for the hard work of digging trenches.

Horace Fort ’14, studying at Berkeley Divinity School, volunteered for the YMCA. He was —unusually—sent to the British Army in India. In the world war more than a million Indian troops were deployed to the Western Front, Gallipoli, Mesopotamia (battling the Ottomans) and East Africa (against the Germans). In India and then in East Africa, Fort was engaged in the YMCA’s welfare work. Whether he worked at YMCA centers for British or Indian troops, it is worth noting historian M.D. David’s judgment that “The YMCA offered programs to help reduce racial tension and promote sympathy for South Asian people and cultures.” And even more broadly, “The YMCA worked to reduce conflict between European troops and indigenous populations, and to prepare for a more egalitarian post-war order.”

Toward the United Service Organizations

The ARC and the YMCA were the most prominent of what would now be called “service organizations” supporting the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and the war effort. The YMCA’s Protestant character, however, rubbed other faiths wrong; they organized similar, though necessarily smaller, efforts.

Beginning three days after the declaration of war, for instance, the Jewish Welfare Board (JWB) organized many programs for Jewish soldiers in the U.S. and overseas. It edited a prayer book that bridged the views of different branches of Judaism, provided kosher food in barracks and its own canteen huts, and sponsored dances, entertainments, classes and literary clubs. Rabbi Leon Spitz ’15 was an auxiliary chaplain sponsored by the JWB at Army camps in Georgia and the New York area.

There were seven service organizations active in France: the YMCA, the YWCA, the National Catholic Council, the Jewish Welfare Board, the War Camp Community Service, the American Library Association and the Salvation Army. As the war ended, they all joined in a United War Work Campaign, which provided the basic concept for the United Service Organization (USO), established in early 1941.

In Retrospect

In this series, I have written of Trinity men for the simple reason that Trinity was then a men’s college. When we speak of the American Red Cross, the YMCA, the Jewish Welfare Board and the other service organizations during the First World War, however, it would be remiss to not recognize how important women were to their work. More than 18,000 ARC nurses served in France, and 12,000 more women volunteers worked at military hospitals, camps and canteens. More than 5,000 women served in France with the Young Men’s Christian Association, and hundreds of women served overseas under JWB auspices.

The military camps in the U.S. and the units of the American Expeditionary Forces were very much men’s worlds, no doubt, but the men saw women in new settings—capable, committed, and dedicated to the nation. The service of these women surely contributed to passage of the 19th Amendment less than two years after the armistice.

This article is the 10th part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part nine, click here. Part 11 will be released Jan. 19, 2025.

+ There are no comments

Add yours