Jackson Loze ‘24

Staff Writer

In this week’s philosophy club meeting, the question “what makes something funny” was investigated. The meeting started with a discussion aimed at categorizing all the empirical examples of laughter the group could come up with. This yielded two distinct groups: intentional laughter and unintentional laughter.

Intentional laughter includes moments when you laugh, not because you thought something was funny but instead to conform with social conventions. Examples of this include laughing at your boss’s joke because you want them to view you more favorably or laughing at your friend’s unfunny “joke” to boost their confidence. Lastly, laughing to look as though you understand a joke everyone else is laughing at also fits here.

Unintentional laughter, as the name suggests, includes moments when you laugh involuntarily. Examples of such laughter include seeing an animal fall in a clumsy and seemingly non-injurious manner. Also, laughter provoked by traumatic experiences, such as being tickled, would also fit into this category.

In trying to determine whether intentional laughter should be considered legitimate laughter at all, the club was unable to reach a consensus. In support of intentional laughter, it was argued that someone who is in a really bad mood often will not be able to unintentionally express any positively charged emotions, causing them to resort to intentional laughter in order to express their genuine reaction to something humorous (I.e., a grieving widow laughing during a funeral speech). In opposition, the argument was presented that the majority of intentional laughter is not really laughter at all; instead, it was suggested that intentional laughter is really just a noise humans make that kind of sounds like laughter.

After categorizing empirical examples of laughter, the club considered 3 different theories of laughter, which claim to explain why we find things funny.

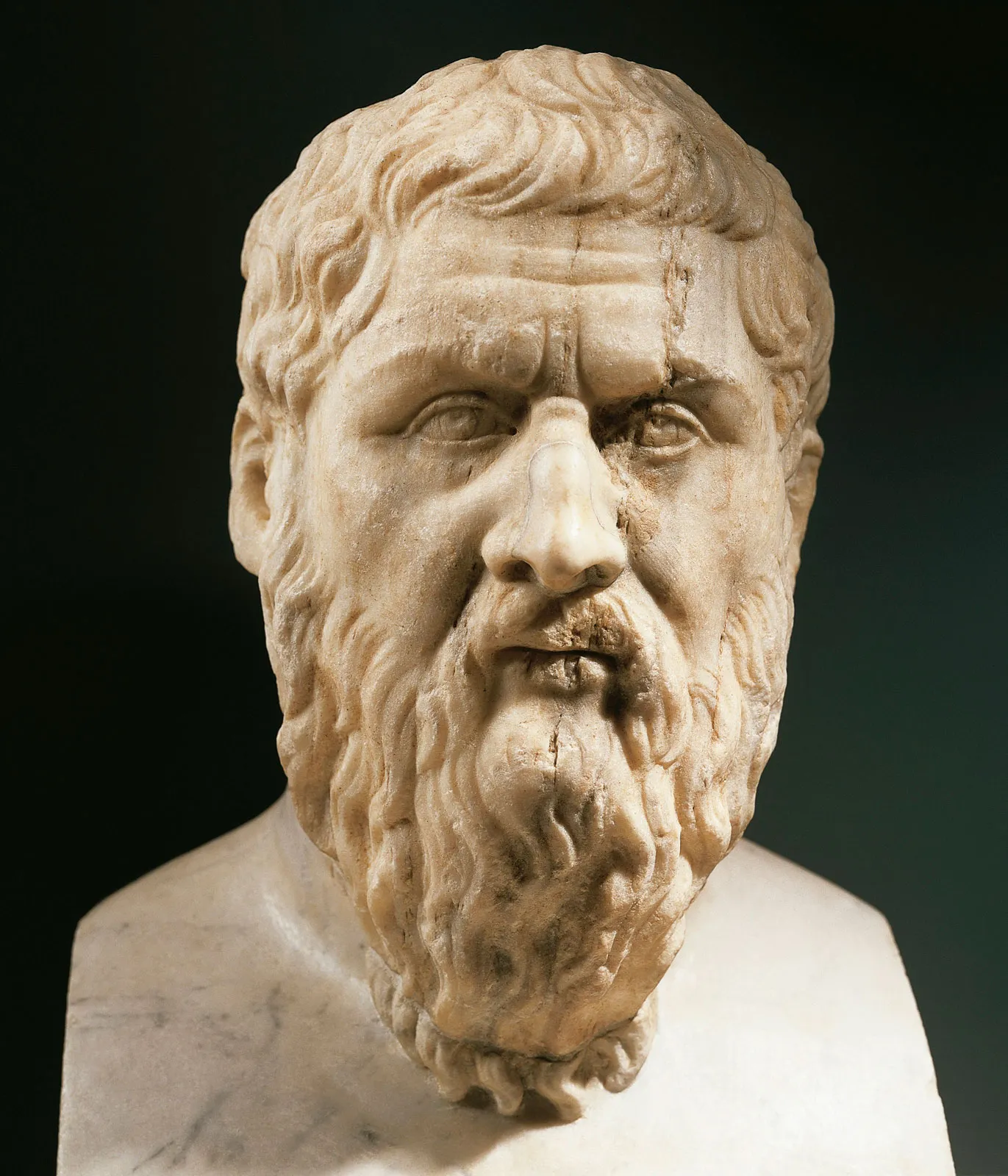

Firstly, the club considered the Superiority Theory, which was advanced by Plato, Aristotle, and Hobbes. Simply put, this theory posits that our laughter expresses feelings of superiority over other people or over a former state of ourselves. A contemporary proponent of this theory is Roger Scruton who analyses amusement as an “attentive demolition” of a person or something connected with a person. “If people dislike being laughed at,” Scruton says, “it is surely because laughter devalues its object in the subject’s eyes.”

Secondly, the club considered the Relief Theory of humor which was advanced by philosophers like Freud. Essentially, “The Relief Theory is a hydraulic explanation in which laughter does in the nervous system what a pressure-relief valve does in a steam boiler.” While not commonly taken to be a proponent of the Relief Theory of humor, the club correctly, in my opinion, decided that Adorno’s assessment of humor best fits here; in the Culture Industry, Adorno suggests that the function of laughter is to alleviate the revolutionary desires and tendencies of the masses living in a capitalist economy by constantly distracting them with amusement and laughter.

Lastly, the club considered the Incongruity Theory of humor, which was advanced by Kant, Kierkegaard, and the majority of contemporary philosophers that are still commenting on humor. Proponents of the Incongruity Theory will typically say that it is the perception of something incongruous, something that violates our mental patterns and expectations, that causes us to laugh. In a unanimous 12-0 decision, the club agreed that this theory of humor had the most explanatory power of the three.

To attend future philosophy club meetings, please contact our president, Charlotte Bond ’23 (charlotte.bond@trincoll.edu).

+ There are no comments

Add yours