Brendan W. Clark ’21

Editor-in-Chief

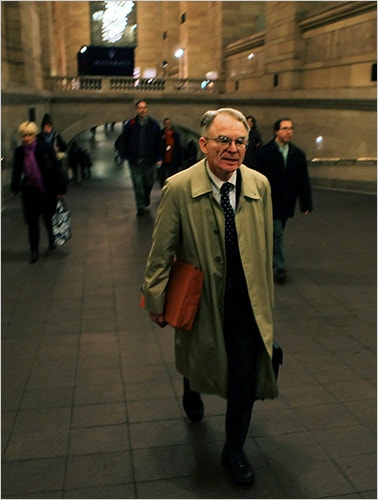

H. Rodgin “Rodge” Cohen—a familiar name to those here at Trinity who have studied Wall Street, banking regulation, and the legalities of the 2008 Financial Crisis—is a seminal player on Wall Street and the world of financial regulation. The senior partner and former managing partner of Sullivan and Cromwell, LLP, a major New York full-service law firm, Cohen has seen a long tenure in S&C’s bank regulatory division since joining the firm in 1970.

The Tripod spoke with Cohen in September, seeking to gain insight from a practitioner on “big law” in New York and how aspiring lawyers can channel their work in law school and enter practice in the field of bank regulation.

From the beginning, Cohen told the Tripod, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do after College. “I considered teaching,” Cohen added, and he “valued his liberal arts education at Harvard.” Ultimately, Cohen noted, the “closest approximation” to continuing that education was law school. After graduating from Harvard Law School, he served in the army and worked on legal matters before entering the world of a New York firm.

Cohen’s shift into bank regulation—where he would eventually leave a significant mark—was to some degree a result of chance. After joining S&C, Cohen learned that two associates were leaving the banking group. When asked to join the team, Cohen recalled that he “didn’t know anything about banking,” but expressed that “he would learn.”

Law school “without a doubt teaches you about how to think.” However, Cohen stressed that bank law and regulation, during his time in law school, was not an area of focus. “I don’t think there was a course offered on that in law school.” Instead, learning the practice was a matter of “observation and being involved in matters where you could take a leadership role.” Cohen noted that that tradition of leadership and involvement is one of the many things he is proud of at S&C, where the culture ensures “associates have many roles” and “regularly engage with clients.” Having the opportunity to engage with client-facing roles, for Cohen, is critical as “so much of the law involves speaking with people.”

Banking practice in the 1970s was “very much loan work and loan origination,” and in those early days the focus was also on “clearing houses” (exchanges which facilitate the sale of securities and derivatives). In those meetings, Cohen “didn’t yet have a seat at the table, but did have a seat in the room,” which was tremendously important for his growth at the firm.

From Cohen’s start, he saw that the practice area “changed as the needs of the industry grew.” These developments were very much the “function of the needs of clients.” Indeed, as Cohen grew at the firm, he saw a change in the pace and spirit of the industry, referencing the “old adage that bankers practiced the 3-6-3 rule” (bankers gathered deposits at 3%, lent them at 6%, and were on the golf course by 3:00). “How true that was, I’m not certain,” Cohen added, though he did note that there was an increasing role for legal and regulatory practice in the industry.

By the dawn of the financial crisis in 2007, when Cohen had been managing partner at S&C for more than five years, the firm counted among its clients leading investment banks and financial firms in the United States: Bear Sterns, J.P. Morgan Chase, and American International Group (A.I.G.). Cohen described the collapse of mortgage issuer Countrywide Financial as the first sign of the crisis, describing it as a “wake-up call” that portended the larger financial instability that followed.

S&C, under the direction of Cohen, would later oversee the acquisition of Bear Sterns and the acquisition of Washington Mutual by J.P. Morgan. S&C was also instrumental in facilitating the provision of government-backed assistance for A.I.G. in 2008, among numerous other deals. Cohen described the process in 2008 as one where he and others were “making a lot of ad hoc decisions,” because “nobody had ever seen anything of this scope before.” Still, the structure of the firm—Cohen believes—helped to ensure that deals could occur and that the tremendous amount of work could be completed. Cohen was able to focus on bank regulation because he knew that he could “rely on other skilled senior partners” for management of the firm itself.

2008 was “certainly a lot of negotiation,” Cohen added, acknowledging that “sometimes you don’t have much leverage.” Still, the full-service nature of a firm like S&C allowed for many “skilled lawyers” to be employed throughout the restructuring process in practice areas of bankruptcy and restructuring. S&C has “a lot of talent and has been fortunate to retain that talent,” Cohen added, crediting many associates and partners with the important restructuring work in the wake of the crisis.

For students and future practitioners, Cohen stressed the value of finding a firm that values you. As one litmus test, Cohen suggested practitioners consider this: “Does the firm not merely permit, but encourage associates to meet with clients?” If you don’t get to participate in meetings, you’ll be “a partner without all of the skills.” Ultimately, good lawyering for Cohen is centered around the value of relationships. They are “essential” for the success of any practitioner and these communication skills are important “most of all” in fostering trust as a counselor.

The firm atmosphere, too, often provides an opportunity to engage in “legal and intellectual debates.” Cohen, who has engaged in law review articles and op-eds in numerous publications, noted that S&C tries to encourage that intellectual interest, especially among partners, as the “more senior you become, the much more likely it is that you have a wider platform.”

Concluding our discussion on the topic of client relations, Cohen noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has upended the legal industry too, changing how these interactions occur. While it is “certainly different” to work with the “imperfect medium of Zoom,” Cohen stressed that people “do adapt” but lamented the loss of “seeing your colleagues in the office.” That is “essential” to professional development and engagement with complex legal issues. Still, S&C—Cohen estimates—“suffered far less than small businesses who contend now with the loss of the consumer.”

As students, firms, and many others ponder their work and their futures, Cohen struck a more positive note, asking English Romantic poet Percy Shelley’s perennial question: “if Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?”

This interview—the first in a series of articles in the Tripod’s “Lawyer’s Corner” by Editor-in-Chief Brendan Clark ’21—examines career opportunities in the legal field by engaging seasoned professionals who have had a significant historical impact in their respective practice areas.

+ There are no comments

Add yours