Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

The nation entered the war. A great mobilization began. The National Guard deployed. A new National Army trained. Carried by the American and British Merchant Marines and protected by the two navies, the divisions sailed through the U-boats to reach France. They were first introduced to the trenches in “quiet sectors,” though some proved not so quiet. The German offensives of 1918—powered by the movement of many divisions from the Eastern Front after Russia surrendered—bloodied the leading Army and Marine Corps units. But the Americans helped stop the German advances.

St. Mihiel: Sept. 12-16, 1918

In September of 1918, Americans took over several miles of the Western Front in Lorraine and at last concentrated for large offensives. On Sept. 12, 1918, half a million Americans in the American First Army attacked a large bulge in the German lines, the St. Mihiel salient, defended by eight German divisions backed up by five more in reserve. The salient was reduced in four days.

Pershing commanded. Sent to the First Army staff, George Marshall helped plan the offensive. Douglas MacArthur commanded a brigade of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division. Harry Truman led an artillery battery from the Missouri National Guard in the First Army’s reserve. George Patton took the first American tanks into combat. Billy Mitchell arrayed the Air Service over the battlefields. John Lejeune led the 2nd Division with its Marines. An obscure crack shot from Tennessee, Alvin York, was in the 82nd “All American” Division. And Trinity alumni joined the offensive.

The largest group of Trinity alumni were in the 26th “Yankee” Division and its 101st Machine Gun Battalion, which attacked the salient from the northwest and met the patrols of the 1st “Big Red One” Division, coming up from the south in a pincer movement, on Sept. 13. But Bantams could be found across the entire front.

Hartford’s James Landon “King” Cole ‘16 played football and captained the hockey team at Trinity, and he was his class’s president. Unusually, he served on the staff of a famous Alabama regiment, the 167th Infantry, in Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur’s brigade of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division.

First Lieutenant Parker Vanamee ‘07—an Episcopalian clergyman who left his parish in Essex, Connecticut, to train at Plattsburg and became an infantry officer—commanded the Machine Gun Company of the 23rd Infantry Regiment in the Army brigade of the 2nd Division. He was wounded in the assault on the first day, dying three weeks later.

Trinity’s Marines in the 4th Marine Brigade joined the assault of the 2nd Division—Private William Lawrence Peck ’17 and First Lieutenant William Washington Brinkman ’15.

Edward Bulkeley Van Zile ’11 served in the headquarters troop of the 5th “Red Diamond” Division in France. In 1918 it fought in the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives, and he was wounded (his father, Edward Sims Van Zile ‘84, was a war correspondent in France).

Private Leon Ransom Foster ’11 served in the 343rd Field Artillery Battalion of the 90th Division. It fired its 75mm guns both at St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne.

In the 301st Engineers, Howard S. Porter ’08 began as the regimental adjutant, but in the offensive, Major Porter led the 2nd Battalion.

After graduation, Trinity football captain John Strawbridge ’95 (“The Iron Duke”) had served in Puerto Rico during the war with Spain. In the First World War he served in the 3rd Battalion of the 319th Field Artillery. It pounded enemy positions in the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives as part of the 82nd “All American” Division.

Stuart Harold Clapp ’05 was in the “automobile business” when the U.S. entered World War I. Joining the Army, he was a lieutenant in 1917 and a captain in 1918. His unit, the 65th Coast Artillery, was raised on the Pacific Coast, transited the Panama Canal, and eventually deployed to England and then France. It was the only American unit firing 9.2-inch British howitzers. Clapp was its ordnance officer, providing and moving the munitions as the unit was attached to the 82nd, 90th, 26th and 29th Divisions throughout 70 days of combat.

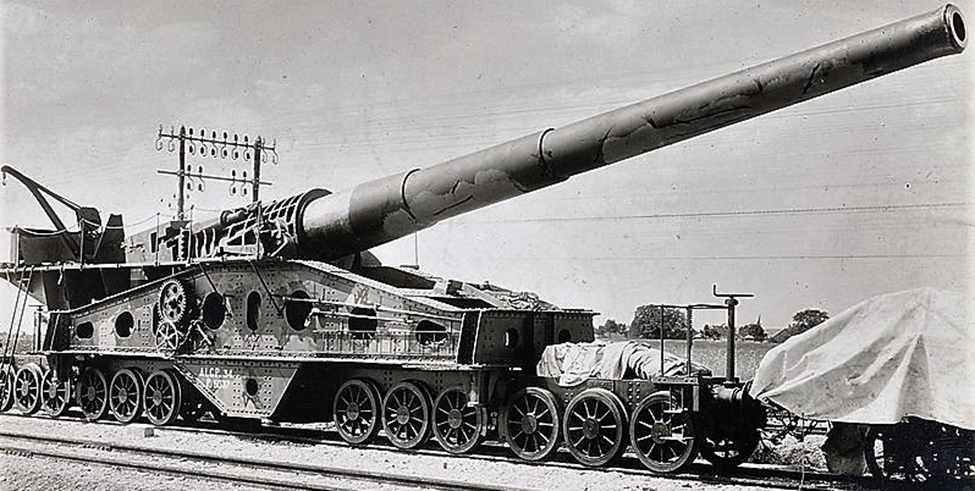

Colonel Jairus Alpheus Moore ‘97 of the 53rd Coast Artillery Regiment led batteries of the AEF’s Railway Artillery Reserve, firing huge 340mm rifled cannons mounted on railroad cars.

Needing to conceal its units from aerial observation, the Army recruited and gathered designers, scene painters, sign painters, architects, landscape gardeners, artists, sculptors and architects at Plattsburg for a new Camouflage Corps. Private Bion Hall Barnett ’12 deployed to France in the 40th Engineers (a captain in the unit was Homer Saint-Gaudens, son of the sculptor). Coloration along with nets and covers could mask weapons, roads and troops.

After enlisting in Troop B of the Connecticut National Guard a week after the declaration of war, Paul Humiston Alling ’19 was frequently transferred—to the 102nd Machine Gun Battalion, the 3rd U.S. Cavalry and the AEF General Staff. He guided French and British military officers observing the 2nd and 5th Divisions during the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives After the war he joined the U.S. Foreign Service, and he served as the first U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan.

Before the Battle of St. Mihiel, American units had always been part of larger operations commanded by French or British generals. The successful reduction of the salient not only caused a German withdrawal from positions they had held for four years; it also demonstrated that the Americans could launch large offensives on their own. Trinity alumni threw their weight on the scale.

This article is the 11th part of a series. For part 10, click here. For part 12, click here.

[…] part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part eleven, click here. Part 13 will be released Feb. 2, […]

[…] This article is the 10th part of a series. For part nine, click here. For part 11, click here. […]