Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

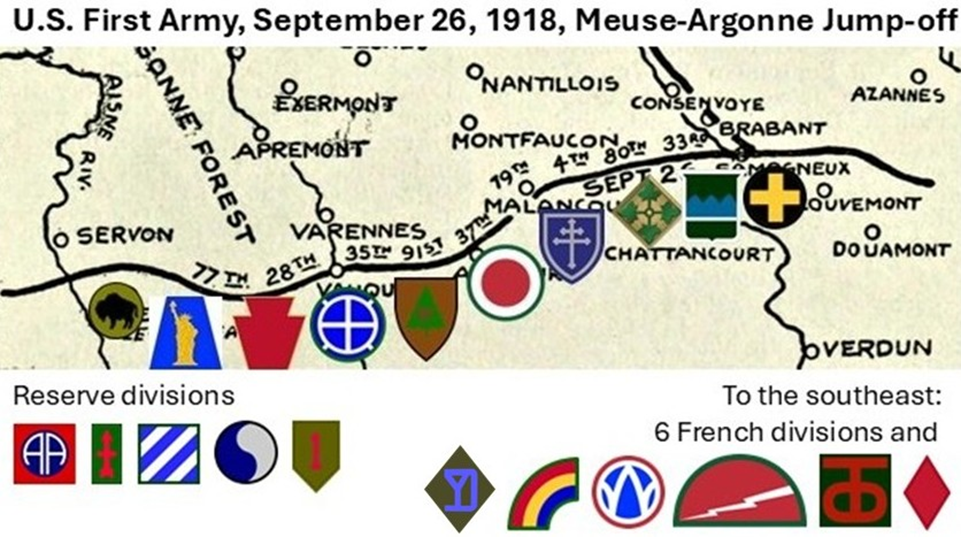

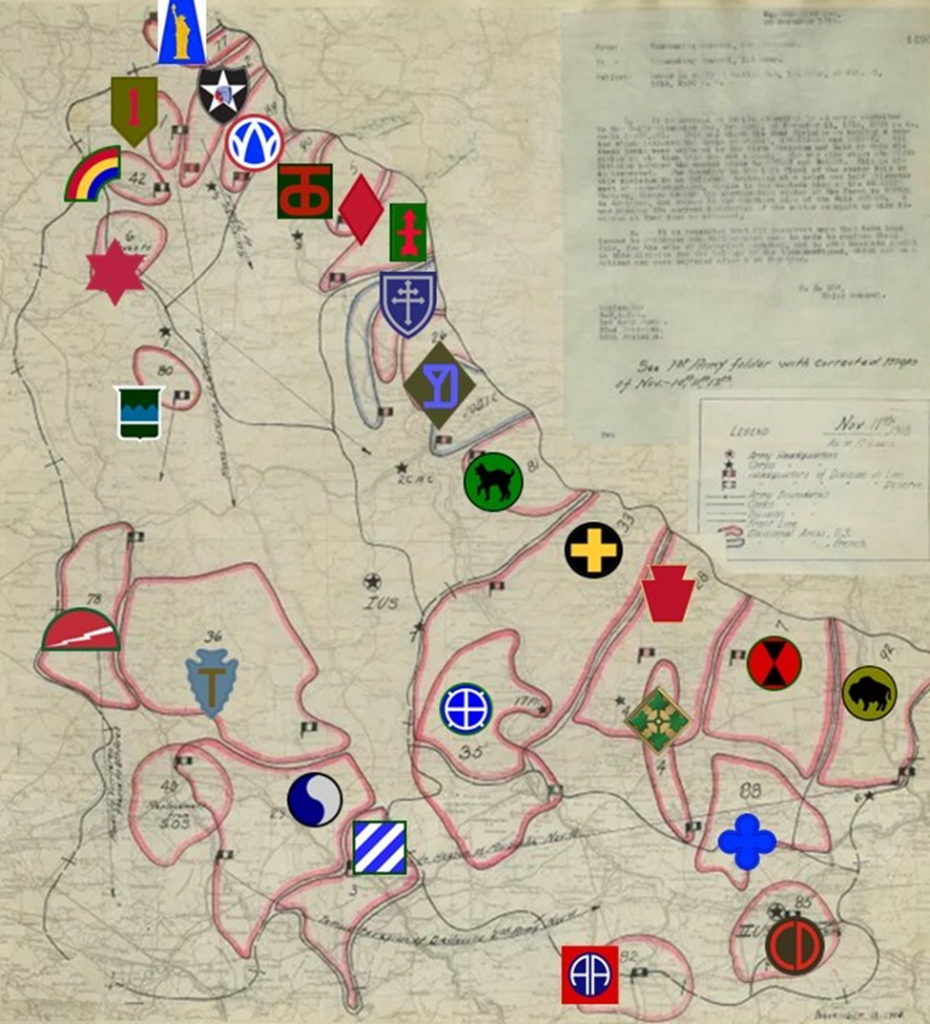

Almost all the American divisions that fought at St. Mihiel were promptly moved west to join the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (“the Argonne”), which began only ten days later. By then, several new American divisions had also reached the front. The First Army’s jump-off was on Sept. 26, 1918, and the offensive lasted until 1100 hours on November 11—the Armistice.

Just previously, the 6th Division—Brigadier General James B. Ervin ’76 commanded its 12th Infantry Brigade—made noisy, visible marches in another sector, aiming to deceive the Germans about the location of the planned offensive.

The Main Attack

General Pershing aimed to launch a powerful offensive, break through the German lines, sever German logistics by cutting the railroad hub at Sedan and force the German Army to retreat and surrender.

79th Division: The “Cross of Lorraine” Division’s first combat was in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, and its objective was to take the commanding heights of Montfaucon. The entire American advance depended on first taking this high ground.

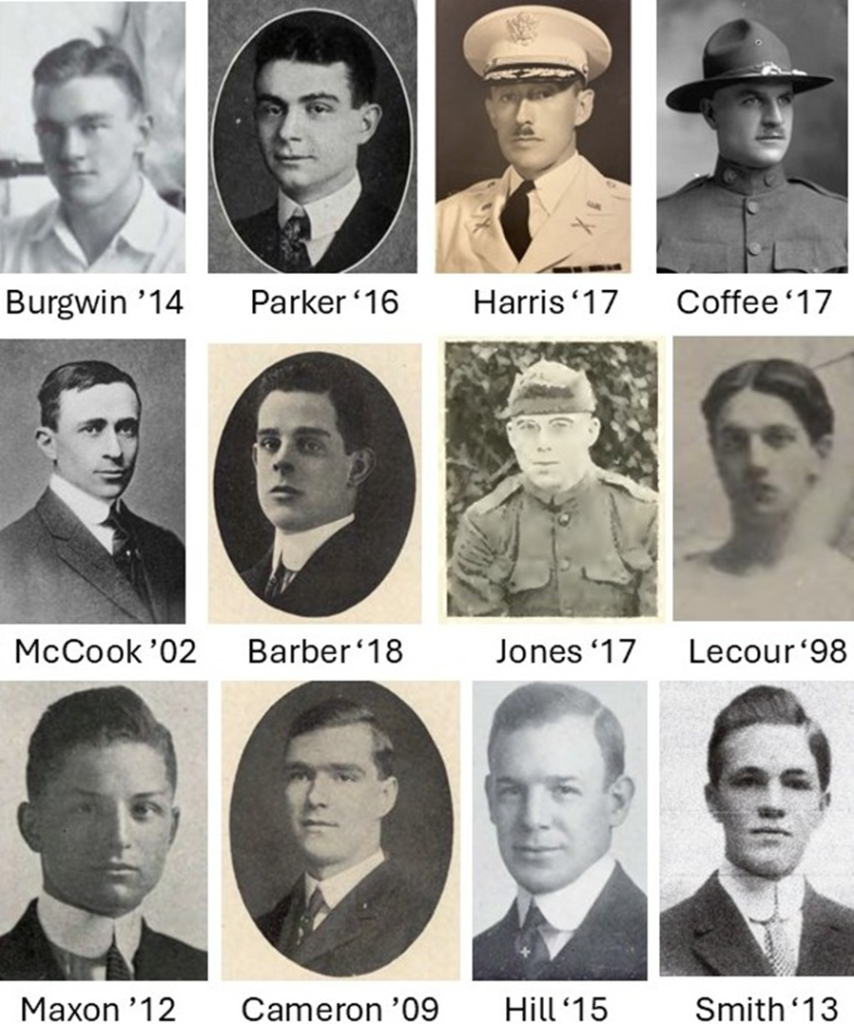

In the fierce combat, casualties among senior officers made Captain George Collinson Burgwin ’14 commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 316th Infantry Regiment. First Lieutenant John Martin Parker ’16, “a shark in Mathematics III” at the College, was in the assault in the 313th Infantry Regiment.

Lieutenant Robert Van Kleeck Harris ’17 had originally deployed to France with the 102nd Infantry Regiment of the Yankee Division, but he was wounded in June 1918. In the Argonne he was in the new Tank Corps supporting the 79th Division’s fight for Montfaucon. Colonel George Patton laid down this rule: “AMERICAN TANKS DO NOT SURRENDER.” Harris received the Croix de Guerre for bravery in “Shrapnel Valley.”

In a murderous two days, the Division achieved its goal at a heavy cost, and the division had to be withdrawn from the front to reorganize. They re-joined the offensive in hills east of the Meuse River.

77th Division: First Lieutenant Vertrees Young ‘17 was the Acting Division Ordnance Officer of the first division of draftees to be sent to the front. He kept the munitions moving as it advanced 22 miles through the heart of the nearly impenetrable Argonne Forest on the far left of the First Army front. Later a noted business executive in Louisiana, he would receive Trinity’s Eigenbrodt Cup in 1970.

80th Division: Sergeant Maurice Dodson Coffee ‘17—a sharpshooter, scout and sniper— fought with Company A of the 317th Infantry Regiment in the “Blue Ridge Division.” The Division’s machine gunners were among the very few who fought with the new American-made Browning .50-caliber machine guns. First Lieutenant Harold Benson Thorne ’16 was an officer in the 315th Machine Gun Battalion.

Valedictorian of the Class of 1902, Anson Theodore McCook ’02 attended Harvard Law School, practiced in Hartford and became active in the National Guard, including service in Connecticut’s Troop B. When Captain McCook deployed to France and served with the 80th Division in the offensive, he was wounded in the arm. After the war he was active in Hartford legal circles and politics, running unsuccessfully for Mayor of Hartford and for the House of Representatives. He received Trinity’s Eigenbrodt Cup in 1957.

28th Division: George Harmon Barber ’18 had served in the New York National Guard on the border with Mexico in 1916. He was later commissioned in the field artillery at Plattsburg. He was aide-de-camp to general officers in the “Keystone Division.” Anyone who thinks being an aide is cushy (especially in combat as commanders must resolve conflicting intelligence coming in by telephone, runners and pigeons, pivot troops as orders come in from headquarters, give orders, and make life and death decisions during hectic operations) should think again.

All four of Trinity’s noted Clement brothers had been officers in the Pennsylvania National Guard before the war. Two were in France: Charles Francis Clement ’05 became the division’s Provost Marshal and commander of the 28th Military Police Battalion, and later he was Assistant Chief of Staff (G-3) of the Division. And Captain Theron Ball Clement ’17 was Assistant Division Quartermaster. Providing and moving materiel for the regiments and battalions engaging the enemy was an enormous undertaking.

78th Division: A past captain of Trinity’s baseball team, Alfred Joseph L’Heureux ’13, served in the “Lightning Division.” Arriving in France in June 1918, it was the reserve division for the I Corps at St. Mihiel. It entered the front line for the Meuse-Argonne offensive on Oct. 16, and it advanced 24 kilometers. Wounded in action, L’Heureux was awarded the Purple Heart, and he was a major and Acting Adjutant of the division at the end of the war.

89th Division: Lewis Gibbs Carpenter ’09 spent two years at Trinity and then worked in investments. In the “Middle West Division,” he was a captain in Battery D of the 340th Field Artillery. During its fights the 89th Division suffered heavy mustard gas attacks in both the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives. Carpenter was wounded on the last day of the war.

6th Division: Bern Budd ’08 was a captain in the 52nd Infantry Regiment of the 12th Infantry Brigade (commanded by Brigadier General James B. Ervin ’76), which joined the offensive in its last 11 days.

To the Right

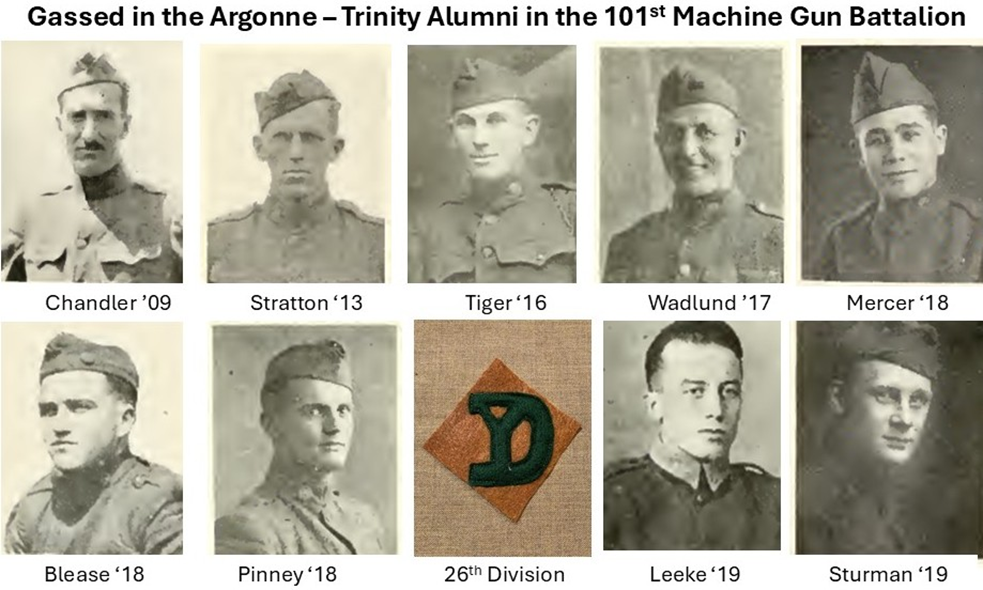

26th Division: At the outset of the offensive, the “Yankee Division“—with dozens of Trinity alumni in its regiments and the 101st Machine Gun Battalion—was the center division in the French Second Colonial Corps, next in line on the right of the main American attack, facing difficult ground. On Sept. 26, the Division’s drive met fierce resistance and moved back, but it deceived the Germans into shifting troops away from the main assault. It again attacked on Oct. 21.

In October, these Trinity alumni in the 101st Machine Gun Battalion were felled by mustard gas: Corporal Harold Nathaniel Chandler ’09, Corporal Reuel C. Stratton ’13, Sergeant Elmer S. Tiger ’16, Corporal Arthur Pehr Robert Wadlund ’17 (later to be Professor of Physics on the Trinity faculty), Private First Class Douglas A. Blease ’18, Sergeant Sydney Dillingham Pinney ’18, Corporal Stanley H. Leeke ’19 and Corporal Everett Nelson Sturman ’19. Fortunately, none died.

Wounded by shellfire the same day was Private First Class Allen Northey “Foggy” Jones ’17; he would receive the College’s Eigenbrodt Cup in 1947 (Jones Residence Hall bears his name).

29th Division: Joseph Henry Lecour, Jr. ‘98 was quarterback of the 1897 Hilltoppers football team and captain of the track team. After training at Fort McClellan in Alabama, First Lieutenant Lecour’s 112th Heavy Field Artillery Regiment deployed to France with the “Blue and Gray Division,” in action for three weeks in the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

32nd Division: William Cassatt Coleman ’09 served with the 147th Field Artillery. Initially, the unit provided theatre training to 22,000 artillery replacements. In the Argonne, it went into action attached to the “Red Arrow Division,” firing more than 56,000 artillery rounds in the assault on the Hindenburg Line. In the Division’s 121st Field Artillery, Francis Joseph Bloodgood ’18 was sergeant major in the Headquarters Company.

92nd Division: Paul Maxon ’12 was captain of Trinity’s track team and served as part of the 328th Field Artillery Regiment, assigned to the (segregated) 92nd Division known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” For most of the war, the 92nd Division was assigned to French commands, but it now became part of the VI Corps of the U.S. Second Army. In the Marbache Sector on the extreme right of the U.S. advance, Maxon’s artillerymen laid down fire as the Black soldiers of the Division advanced in the last few days of the war.

I Corps: Captain Ralph Evelyn Cameron ‘09 played football and basketball at Trinity, and at graduation he was awarded the first Mackay-Smith Mathematics Prize. He served in the 114th Engineers and was assigned to the I Corps reserve, which joined the Meuse-Argonne offensive for an intense twelve days until the end of the war.

This series of articles—so many names, units, dates and places—shorts the difficulties and agonies faced and overcome by all the units in battle. The 1920 history of the 26th Division describes some of them: “the high, frowning ridges, seamed and scarred and blasted … the ragged woods with their nests of machine guns, minenwerfers [mortars that fired short range mine shells], and heavy wire … the difficulty of an advance over a country of steep slopes, confusing ravines, and deep mud, in the face of a determined resistance by troops told off to hold these woods and ridges to the end.” Added to this were the deadly hazards of German snipers, grenades, smoke, poison gas and observation from aircraft and balloons that pinpointed the location of American units for artillery bombardment. And in the autumn of 1918, the influenza epidemic began to thin American units.

And In Italy

In 1918, the Italian Army was in a desperate struggle against its Austro-Hungarian foes. Italy called for U.S. troops; the 332nd Infantry Regiment was sent to Italy, visibly marched back and forth across the front to deceive the enemy into thinking a sizable American formation had arrived, and participated in the culminating Battle of Vittorio Veneto. First Lieutenant Howard Rice Hill ’15 was awarded the Italian War Cross.

Also receiving the award for valor was Captain Ethelbert Talbot Smith ’13. He commanded Section 37 of the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps with the Italian Army. “With only 12 ambulances at his command” during the battle, “he rescued 2,000 wounded under circumstances of extreme peril.”

The Costs of Victory

Americans mourn the death of service members in recent wars—4,419 in Iraq in eight and a half years and 2,459 in Afghanistan in just under 20 years. In the year and a half of U.S. participation in the First World War, the armed forces suffered 116,516 dead, at a time when the nation’s population was 103 million people (compared to 329 million in 2020).

Three-fourths of American combat deaths occurred in the last three months of the war. In the 47 days of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the AEF suffered 26,277 deaths among more than 120,000 total casualties. It remains the deadliest campaign in American history. The scale of these losses did not sink in until after the victory, but their memory powered much of the American isolationism in the years before World War II.

That said, the Meuse-Argonne offensive—spurred by the enormous mobilization of industry, the economy and the expansion of the armed forces in a year and a half—established the U.S. as a global superpower. And one small college in Connecticut had answered the call.

This article is the 12th part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part eleven, click here. Part 13 will be released Feb. 2, 2025.

+ There are no comments

Add yours