Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

The Honor Roll published in the 1920 Ivy listed alumni who received significant awards for bravery—from the U.S., France and Italy. More research has yielded additional names.

The highest medals for heroism awarded to Trinity men were the nation’s second highest after the Medal of Honor: the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and the Navy Cross.

During the war, commanding officers could cite individuals for valor or achievement, paralleling the British “mentioned in despatches.” In U.S. practice, individuals cited at the Division level could place a silver “Citation Star” on their World War I Victory Medal. In 1932, those cited for gallant conduct could apply for the new Silver Star Medal to replace their Citation Star.

Soldiers who were wounded in battle originally wore a wound chevron on the lower right sleeve of their uniforms. In 1932, the War and Navy Departments issued the new Purple Heart Medal to replace the chevrons.

France’s Croix de Guerre was awarded to some Trinity alumni, and stars and palms recognized exceptional bravery. A few Trinity alumni received the Italian War Cross.

Here are the ferocious Bantams.

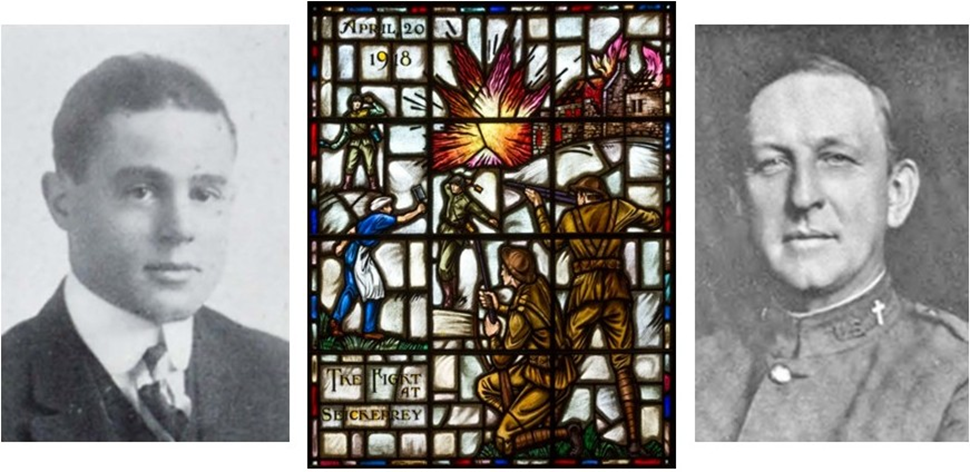

Major William Edward Barnett ’15: Part of the 104th Infantry Regiment’s fight in Seicheprey on April 10, Barnett’s citation for the Silver Star recognized him for “directing his platoon through a heavily shelled area.” As Trinity’s 1920 Honor Roll recorded, he “was in the thick of fighting at Seicheprey, Chemin des Dames, Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel and finally at Argonne Forest, at all times at the head of his platoon or company.” He was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre with star.

First Lieutenant Arthur Ernest Lynn Westphal ’19: When Russia surrendered to Germany in 1917, many divisions of German troops were moved to the Western Front, and in 1918 the German high command launched offensives. They hoped these additional troops could overwhelm Allied defenses before the growing flow of American soldiers could turn the balance of forces against them.

In July a powerful German thrust advanced to within 45 miles of Paris, reaching the Marne River. In the Second Battle of the Marne on July 15, 1918, Westphal was assigned to the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Division near Fossoy. “In command of a Stokes mortar detachment,” read his citation for the DSC, “Lieutenant Westphal displayed marked coolness and leadership under intense enemy shell fire in so operating his guns as to stop the advance of the Germans and prevent their crossing the Marne.” The defense gave the 3rd Division the name it is still called today: “Rock of the Marne.”

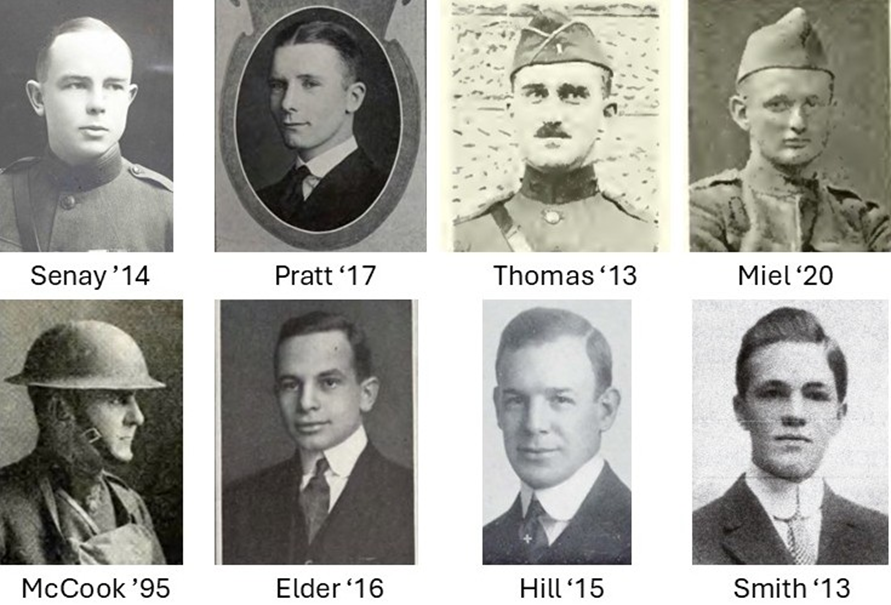

Captain Charles Timothy Senay ’14: American advances followed. In the Battle of Soissons on July 19, Senay was in the 28th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division, the “Big Red One.” He “displayed inspiring courage and leadership under heavy fire during the capture of Ploisy and while reorganizing units and repelling a counterattack,” read his citation for the DSC.

Wagoner Edmund R. Hampson ’18: “Weary” Hampson of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism” near Trugny, France, during the Second Battle of the Marne on July 2. The College’s 1920 Honor Roll provided details: he “made three trips to a dressing station with wounded soldiers. A shell exploded four feet in front of the car he was driving, wounding him in 10 places. He continued at his work until the loss of blood and pain caused him to collapse.” Hampson later drove 3,000 miles as a battalion motorcycle driver.

Second Lieutenant John Humphrey Pratt, Jr. ’17: In August the U.S. 4th Division joined British troops in the “Hundred Days Offensive” that would end at the Armistice. Pratt was decorated for “for extraordinary heroism in action near Bazoches.” His DSC citation read that he “was untiring and fearless at all times in the performance of his duties as liaison officer. Under heavy fire he made three exceptionally hazardous trips with messages of vital importance when other means of communication had failed, volunteering for this service.”

Private James Jellis Page ’08: When Page returned to New York City to join the head office of the Vacuum Oil Company after working in Canada, Hawaii, Cuba, Mauritius and South Africa, he joined the New York National Guard’s Seventh Regiment. He was sent to the Mexican border in 1916, and was again called up in 1917. During the 27th Division’s assault on the St. Quentin Canal-Tunnel on Sept. 29, 1918, he was killed on a daylight patrol to probe and locate German defenses. Page is cited for “valuable assistance in combat in the face of heavy enemy machine gun fire. He was killed going forward.” His award of the Silver Star was posthumous.

Captain Harry Woodford Hayward ’97: Woodford commanded Company E of the 107th Infantry Regiment in the same assault. His divisional citation read that “he advanced his company under extremely heavy shell and machine gun fire until killed.” Stephen L. Harris, in his 2006 history of the regiment “Duty, Honor, Privilege,” told more of the story. “Rushing ahead of his men in E Company, Captain Harry Hayward, who loved the woods of his native Maine, caught a string of explosive machine gun bullets in the groin. The lawyer pitched into a shell hole, his intestines oozing out of the gaping wound …”

Second Lieutenant Robert Wright Thomas ’13: Thomas had been a member of Connecticut’s Troop B and the 101st Machine Gun Battalion. Commissioned in 1918, he subsequently commanded machine gun units in the 5th and 81st Divisions. A 5th Division order cited him: “During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, he directed the fire of his platoon in support of the troops which were attacking on the opposite bank of the Meuse River. Under direct observation of the enemy, he constantly exposed himself, personally directing each gun in its difficult task of overhead fire, thereby furnishing an inspiring example to his men.”

Second Lieutenant James Edward Breslin ’19: During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on Oct. 15, 1918, Breslin fought in the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division. Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur told the regiment that the German defensive stronghold at Cote-de-Chatillon must be taken at any cost. According to Breslin’s citation for the DSC, “held up by intense concentrated machine-gun fire, he courageously led his platoon forward and penetrated the enemy’s lines for a depth of one kilometer, his command being reduced … to only 12 men. In severe hand-to-hand fighting he captured two machine-gun nests and 40 prisoners … which enabled the leading companies to continue the advance.” For this action he also received the French Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre awards from France and Belgium.

Corporal Charles Jan Miel ’20: Those who saw the film “1917” can understand how difficult it was to communicate with adjacent units and with headquarters on World War I battlefields. According to his citation, on Oct. 26, 1918 Miel “distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with Company B, 101st Machine-Gun Battalion, 26th Division, in action in the Houppy Bois, north of Verdun … while delivering a message from company to battalion headquarters. Although his companion was mortally wounded by enemy artillery fire, Corporal Miel successfully accomplished the mission assigned to him.” He received the Silver Star.

Marine Corps First Lieutenant Arthur Houston Wright ’18: Houston received the Navy Cross, cited for “bombing enemy bases, aerodromes, submarine bases, ammunition dumps, railroad junctions, etc.” as part of the First Marine Aviation Force. Wright died of influenza and pneumonia in October of 1918; the medal was awarded posthumously.

Philip James McCook ’95: Upon graduation from Harvard Law School, McCook immediately enlisted as an infantryman for the war with Spain. Rejoining the Army in 1917, he was with the 9th Infantry Brigade of the 5th Division during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. His citation told the story: on Nov. 6, 1918, Major McCook was “sent out by his brigade commander to reconnoiter the enemy’s lines near Lion-devant-Dun and Cote St. Germain … He passed from front-line units to the command post of the 61st Infantry through severe artillery and machine-gun fire in order to telephone the results of his reconnaissance to his brigade commander. While passing through this heavy fire for the third time, he was severely wounded in the right leg by a fragment of shell. Though his leg was broken and he was unable to walk, he refused to be evacuated until assisted to a telephone where he made his report to his brigade commander. He then refused to have his wound dressed until others had received treatment.” In World War II, Colonel McCook traveled 60,000 miles to inspect the treatment of freed American POWs.

Edmund Kearsley Sterling ’99: Two years at Trinity preceded Sterling’s appointment to West Point, from which he graduated in 1901. His career took him to the Philippines and posts in the American West. Sent to France as a Major in the 90th “Tough ‘Ombres” Division in 1918, he rose to command the 359th Infantry Regiment as a Colonel. His Silver Star citation recognized “gallantry in action … without regard for his own life” at Bantheville in November during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

Laurels from France and Italy

Private Ethelbert Wyckes Love ’20: Some decorated Trinity alumni have been mentioned in previous articles in this series. Love was an ambulance driver with the American Field Service, transporting wounded French soldiers to medical care. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre for action on April 3, 1918. He transferred to the U.S. Army later in the year.

Private Francis Wyatt Elder ’16: Elder was part of the U.S. Army’s Ambulance Corps. The College’s 1920 Honor roll recorded that received the Croix de Guerre “for extraordinary bravery in rescuing in his ambulance under heavy fire four wounded Frenchmen. In carrying out this act of bravery he was himself wounded in the right leg by a piece of high explosive shell.”

First Lieutenant Jerome Pierce Webster ’10: Serving under the 1st Gas Regiment, Webster was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Star by the French government. His citation, reported in the regiment’s history, read “A devoted and courageous doctor. In the midst of a violent bombardment he did not hesitate to come to the rescue of French soldiers who had been gassed.”

Chaplain Captain Walton Stoutenburgh Danker ’97: Danker was chaplain of the 104th Infantry Regiment of the 26th “Yankee” Division duing the murderous action at Seicheprey, April 12-14, 1918, cited for “attending the sick and wounded and caring for the dead under enemy fire.” He received the Silver Star and the Croix de Guerre. Killed by artillery fire a month later, he was the first American chaplain to be killed in action in World War I.

First Lieutenant Howard Rice Hill ’15 and Captain Ethelbert Talbot Smith ‘13: Two Trinity alumni received the Italian War Cross. Hill fought in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in the U.S. 332nd Infantry Regiment. And Smith commanded Section 37 of the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps with the Italian Army. Trinity’s 1920 Honor Roll provided details: “With only 12 ambulances at his command” during the battle of Vittorio Veneto, “he rescued 2000 wounded under circumstances of extreme peril.”

There can be little doubt that the valor of other Trinity alumni fighting in France in desperate circumstances were, in both the press and confusions of battle, unrecorded and unrecognized. The alumni who received decorations, however, provide some testimony about the Great War. The rapid mobilization of the United States, war loans, the shipment of material and the deployment of two million Americans to France were surely decisive in bringing the war to an end in 1918. But in the end there were also grim fights and sacrifices, all charged with courage. Trinity alumni in uniform contributed their share.

This article is the 13th part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part 12, click here. Part 14 will be released Feb. 9, 2025.

+ There are no comments

Add yours