Donald M. Bishop ‘67

Alum Contributor

Having reviewed more than two hundred files of Trinity alumni in the First World War, a few stories—some poignant, some tragic—deserve a prominent place in the memories of the College.

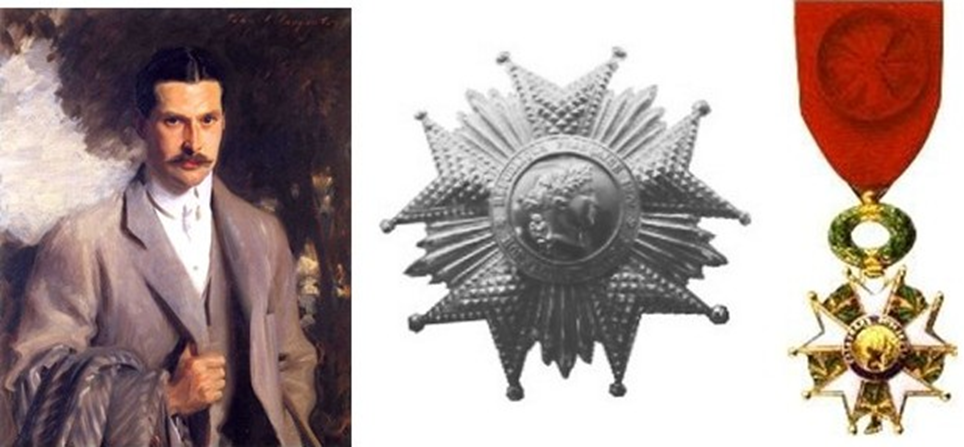

After graduation, John Ridgely Carter ’83 combined careers as an attorney, diplomat and financier. In 1887, he married Alice Morgan (a member of the banking family), graduated from the University of Maryland’s law school and attended Harvard Law, practiced law in Baltimore, and became an American diplomat in London in 1894. After serving as U.S. Ambassador to Romania and Charge d’affaires in Constantinople, he left the diplomatic service to join J.P. Morgan & Co. in New York and then its French affiliate, Morgan, Harges & Co., in Paris. So powerful was the House of Morgan that when war broke out, Carter’s firm guaranteed in gold all checks written by Americans in Europe and honored all letters of credit. It financed “immense loans” to the French government. Carter also became treasurer of the American Red Cross in Europe. France decorated him as a grand commander of the Legion of Honor.

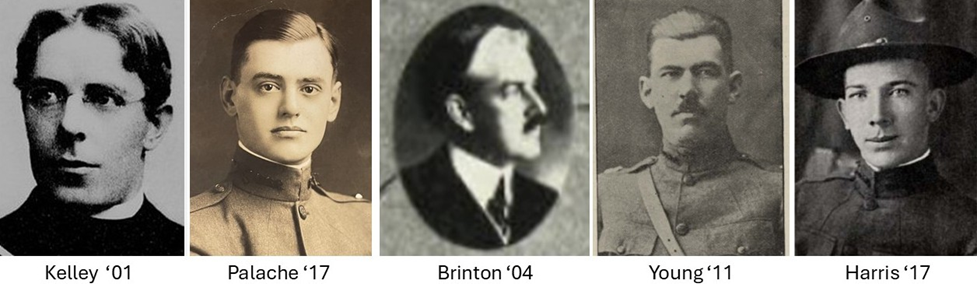

After Trinity, Arthur Paul Kelley ’01 was ordained and ministered in New York, Massachusetts and Nebraska. He relinquished his pastorate to enlist, serving in a Massachusetts ambulance unit on the Mexican border, where he was promoted to sergeant. When the war came, he went to France in the 103rd Ambulance Company of the 26th “Yankee” Division. At the front lines on July 2, 1918, he was stabbed by a German soldier and died of a hemorrhage in the hospital on July 5. A few weeks later, a dead German soldier was found with Kelley’s Phi Gamma Delta pin in a pocket.

The AEF’s 18th Engineer Regiment (Railway) had recruited Pacific Northwest civil engineers, road builders and experts in steel construction, telephone and telegraph lines, bridges, railways, water supply, and training. It reached France early, in 1917. To streamline the flow of supplies to the front, its main projects were dock and departure yard construction at Bassens, laying a third rail track between Bassens and St. Sulpice, and the St. Loubes Ammunition Depot. The unit’s work was greatly aided when Captain Harold Wheeler Young ’11 commandeered—with no authorization—a locomotive, fending off all investigations.

A few weeks before Second Lieutenant James Palache ‘17, a platoon leader in the 18th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, was killed by enemy artillery on May 15, 1918, near Cantigny, he wrote this to his father: “ … the men in the ranks are the most important ones, and what they do, or do not do, counts. To get them behind you, and working with you, is an officer’s only job—once that is obtained, the rest is easy.” Every Trinity alum who ever served—in World War II, Korea, the Cold War, Vietnam, the Gulf, Iraq and Afghanistan—will nod in agreement.

Saving Soldiers in Gas Attacks

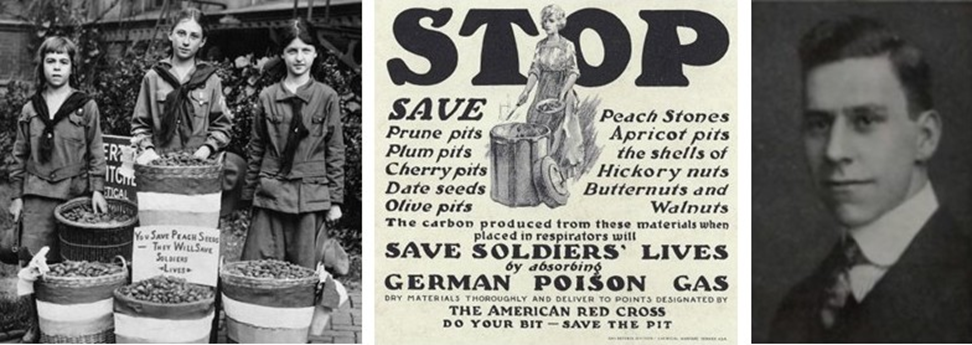

Paul Henry Mallet Prevost Brinton ’04 left Trinity early and continued his education at Stevens Institute of Technology and the University of Minnesota. He was commissioned in the new Chemical Warfare Service during the war. To investigate poison gases and the use of chemical warfare on the Western Front, and to develop protection, he worked in a secret facility at Tomkins Cove near Jones Point, New York. After the war, he taught at the Universities of Arizona and Minnesota, and in retirement became a competitive skeet shooter.

A track letterman who was also the Glee Club’s leader at Trinity, Charles Byron “Hoppie” Spofford ‘16 was also commissioned in the Chemical Warfare Service. When he died in 1968, Trinity’s alumni magazine noted that he “made a distinct contribution in the discovery of an element in peach pits which was used to add to the safety of gas masks used throughout the war.” Boy and Girl Scouts then combed the nation to gather peach pits for the activated charcoal filters in gas masks. He did not deploy to France and see combat, but his work saved many lives. After the war, Spofford was a trade commissioner in India and Denmark, and during World War II he was supervisor for the U.S. Food Administration in southern Florida.

A Final Tragedy

Those who watched the 2022 film, “All Quiet on the Western Front,” based on the 1929 novel by Erich Maria Remarque, felt the futility and waste of lives in the German unit’s attack against the French early on Nov. 11, 1918. Not well known is that there were Americans attacking the Germans that same morning. The message that hostilities would end at 11 a.m. had not reached every American unit.

Early that final morning of the war, Second Lieutenant Edward Cedric Harris ’17 led his platoon in the 321st Infantry Regiment of the 81st Division in the Meuse-Argonne offensive near Grimaucourt, France. His citation for the Distinguished Service Cross recognized his “extraordinary heroism … Lieutenant Harris … and a small number of riflemen, had succeeded in penetrating the enemy’s first line wire and he had mounted his machine gun and opened fire when machine gun fire from the enemy was directed at the party from three sides at almost point-blank range. At this time Lieutenant Harris was wounded.” He “refused to allow his men to render him assistance, saying that if they exposed themselves they would all be killed and ordering them away.” The award was posthumous

Looking Back on the Great War

In 1964, freshmen who had just finished the required Trinity course in world history sat down, pens and blue books in hand, for the final examination. On the blackboard, the prof wrote out a single question: “Why, 1914?”

Scholars and the public still argue about the First World War: its origins, conduct, costs, consequences of the lines drawn on maps at the peace conference and how it shaped—or misshaped—the future. They argue about America’s participation. Even after a century, military historians continue to publish new books with fresh insights on battles, campaigns, mobilization, medical care, technology, logistics, the participation of American minorities and inter-allied cooperation.

Trinity alumni and students, few involved in Washington’s decision to declare war in 1917, rushed to the colors for many reasons. The National World War I Museum and Memorial has it right. “They volunteered for adventure. They volunteered to see the world, even one torn by war. They volunteered for the better good. They volunteered because their friends did. They volunteered because they wanted to make a difference.” Their sense of “better good” excluded “Kaiserism,” the fever of military vainglory, or the militarism that caused peoples to believe their destinies wore uniforms, marched in goose steps, and ruled empires.

So Trinity men learned to march and run the obstacle courses, fire Springfields, machine guns, mortars, and artillery, fly in primitive aircraft, drive ambulances and tanks, face U-boats they could not see from deep inside a warship, perform surgery on men ghastly wounded, pass through machine gun fire and gas attacks, and mourn the loss of comrades.

After it all, they returned to the embrace of families and ordinary lives. At reunions, they enjoyed the peaceful Long Walk even more because they knew from experience that peace can depend on the exertions of preparedness and war.

A Few Historical Notes

Research for the articles in this series began with the College’s Honor Rolls published in the 1919 and 1920 issues of the Ivy. The 1920 Honor Roll lists 517 alumni who served in uniform and 110 more who joined the war effort in other capacities such as the Red Cross and the YMCA. Of those totals, research has yielded more detailed information on about 225 so far.

Sources also include wartime articles in The Trinity Tripod, the College’s biannual “Necrology” issues of the Trinity College Bulletin, the “In Memory” notes in the Trinity’s alumni magazine and The Trinity Reporter and the individual alumni files held in the Watkinson Library—all supplemented by internet searches for obituaries, local histories and genealogical compilations. Find a Grave has yielded obituaries and photographs for many, but not all, alumni.

We tend to think of a college’s “alumni” to mean its graduates, but all students who matriculate at Trinity are alumni of the College. A number of the individuals mentioned in these articles left the College before graduation. On one hand, it was common for students to study in a college or university for only a few years before entering the workforce. On the other hand, students transferred to other schools. And many members of the classes from 1917 to 1920 left the College to enlist. For these alumni, no graduation photos are available in the yearbooks.

The 1919 Honor Roll provided information available to the College in the summer of 1918: if an alumnus was listed as a member of a unit still in the U.S., entries in this series are based on those assignments. Some may have changed, but without access to individual Army, Navy and Marine Corps files, some assignments mentioned in the individual articles may be inaccurate. Some alumni, moreover, shipped out to France in divisions that were subsequently broken up to provide replacements and “skeletonized.” Information on an individual’s subsequent assignments is scant.

I thank Eric Stoykovich of the Watkinson Library, Nick Cimillo of the Tripod staff and Marc Grotelueschen of the U.S. Air Force Academy faculty for their assistance.

This article is the 15th and final part of a series. For part 14, click here.

+ There are no comments

Add yours