Donald M. Bishop ’67

Alum Contributor

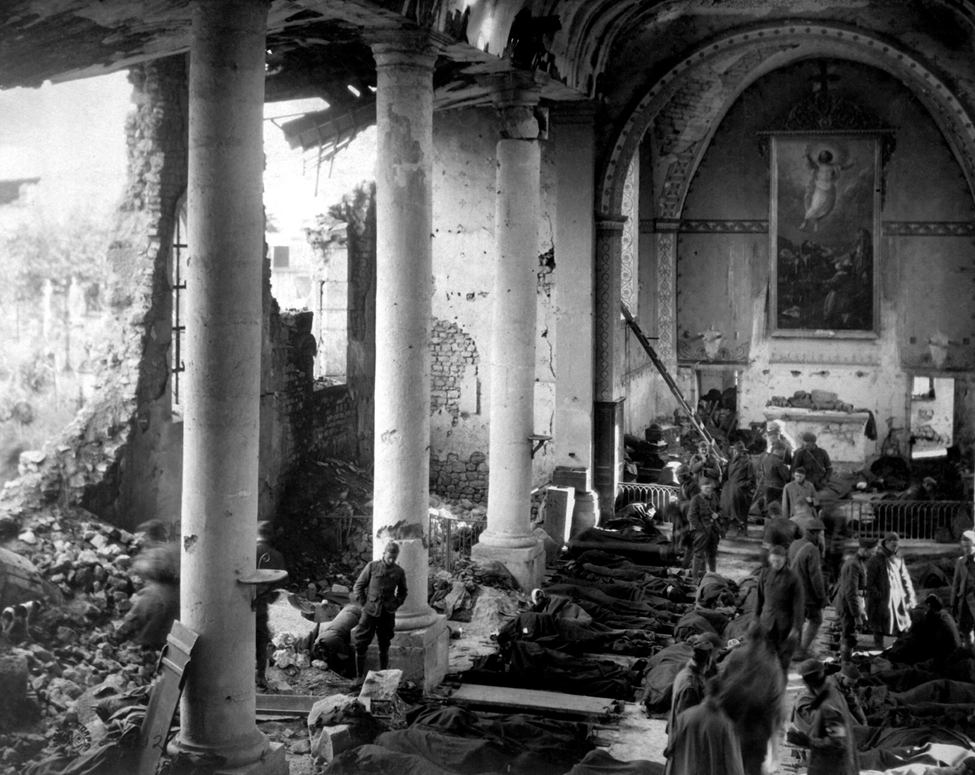

in a church at Neuville, France, Sept. 20, 1918(Photo credit: US Army)

The vast mobilization of millions of American soldiers, sailors and Marines in World War I required a concurrent medical mobilization.

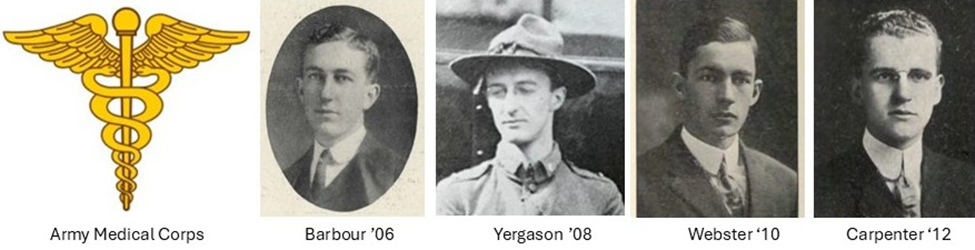

The Army Medical Corps grew to include more than 31,000 doctors—almost a quarter of the nation’s physicians. Counting other medical officers, nurses and enlisted medical personnel, its total strength by the end of the war was 350,000.

In France, many of the medics were assigned to battalion or regimental aid stations or to field hospitals. Others staffed divisional Sanitary Trains which provided emergency medical treatment, triaged the wounded, identified those soldiers who could be moved by ambulance or rail to higher level care. Others were at hospitals to receive and treat them.

Personnel of the Medical Corps treated injuries, wounds, trench foot and then-common infectious diseases like measles, diphtheria, typhoid and scarlet fever. And it faced new challenges when the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 struck soldiers, sailors and Marines—in France and in the U.S.

Trinity “docs” were there. The College’s Honor Rolls published in 1919 and 1920 list 13 medical doctors and 11 enlisted members in the Medical Corps. More than 20 Bantams were ambulance drivers, and other Trinity alumni served in France with the American Red Cross (to be discussed in a subsequent article in this series).

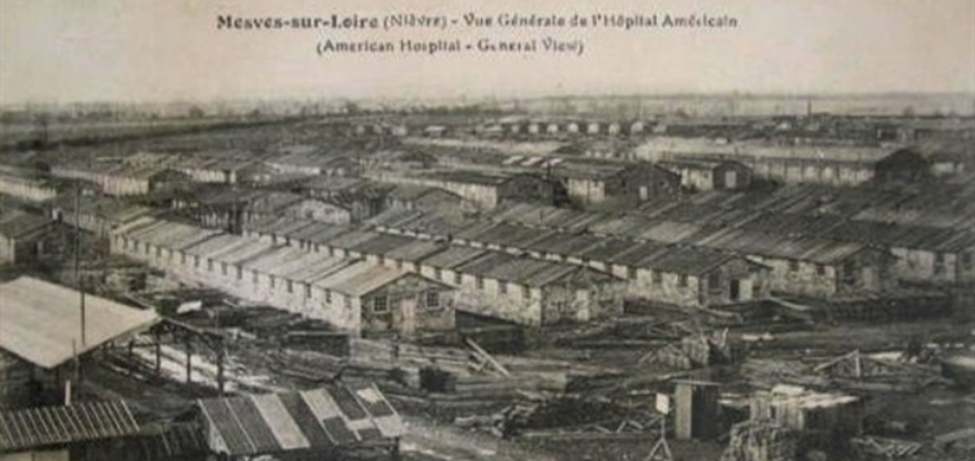

Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright ’95 served in France at Base Hospital No. 54 (in Mesves in the Department of Nievre), becoming its commander and chief of surgical services. The AEF included three lieutenant colonels, all with the same name; the other two were Wainwright’s cousins, all of them named for the same grandfather (and to one fell the duty of surrendering U.S. forces in the Philippines to the Japanese in 1942).

The advent of chemical warfare led the Army to form the 30th Engineers (Gas and Flame), eventually named the 1st Gas Regiment; it fought in the Toul and Chateau-Thierry sectors and the St. Mihiel Offensive. A physician with the unit, First Lieutenant Jerome P. Webster ’10 was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star. His citation credits him as “A devoted and courageous doctor. In the midst of a violent bombardment he did not hesitate to come to the rescue of French soldiers who had been gassed.”

In the U.S., the use of poison gases on the Western Front prompted a whole-of-government response. The U.S. Bureau of Mines—with its experience detecting lethal gases in underground passages—was tasked to study their properties. The Bureau drew on the expertise of the Yale Medical School faculty. Dr. Henry Gay Barbour ’06, who had studied medicine at Johns Hopkins and in Freiburg and Vienna, focused on chlorine.

Captain Robert Moseley Yergason ‘08 received his medical degree from Columbia and served on the Mexican border with the First Connecticut Ambulance Company in 1916. During the World War he was stationed at the Yale Army Medical Laboratory. He was credited for “Yergason’s Test” in biceps tendon pathology and for developing the Yergason screw.

Sergeant Arthur Chadwell Short ’03 was in the Sanitary Train of the 87th Infantry Division. James Fairfield English ’16 was an enlisted medic; his son would become President of the College in 1981.

In the Navy, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) McWalter Bernard E. Sutton ’99 was the medical officer on the troopship USS Kroomland.

In 1918 and 1919, the Trinity physicians, medical officers and corpsmen were increasingly occupied by the influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919. Of the College’s dead in the Great War—the twenty alumni whose names are carved on the wall of Trinity’s chapel—eleven were felled by the pandemic.

Two Reflections

Lieutenant Chapin Carpenter ’12 was a ward surgeon at the AEF’s Base Hospital 34 at Nantes. Over 9,000 casualties were treated at the Hospital, with ever heavier loads as the AEF turned to the offensive in the summer of 1918 and the medical staff also confronted the pandemic. He wrote, “. . . a man who could keep his temper amid the trying work of a ward, and always be cheerful, no matter how sordid and monotonous his tasks, deserved as much credit and honor as a soldier in the front lines.”

Private Clarence Irving Penn ’12 was assigned to Base Hospital 9 in Chateauroux. It became the orthopedic center for bone and joint wounds in the AEF; the work included reconstruction and physical therapy; and many patients had contracted infectious diseases— including, by war’s end, influenza and pneumonia. The history of the unit, written by its chaplain, Raymond S. Brown, included this: “. . . heroism was not finished at the battle line. The days in the hospital were the ones that really proved the stuff of which men are made. Here they would lie day after day. Dreadful gashes had been torn in their bodies, bones had been broken and bruised, arms and legs had been taken from them, yet there was little complaining over their lot. A peaceful spirit seemed to dwell within them—the consciousness of having acquitted themselves like men. Those who suffered most complained the least.”

Chaplains

Trinity’s ties to the Episcopalian Church (eleven of its first twelve Presidents were clergymen) made it a feeder school for graduate study at divinity schools followed by ordination and assignment to churches. Some alumni became chaplains in the regular Army or Navy, while others affiliated with local National Guard units. And more volunteered to be of service when the U.S. entered World War I.

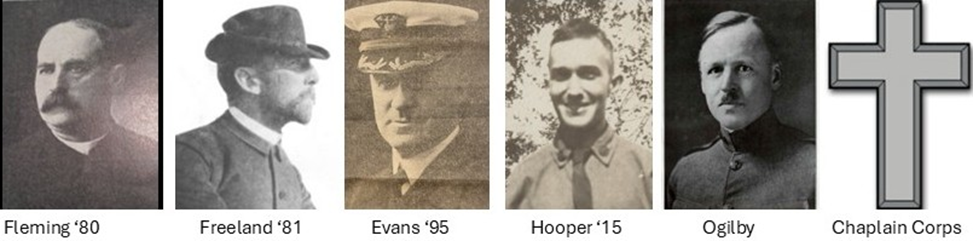

A pastor in Leadville, Colorado when the war with Spain began, David Law Fleming ‘80 became chaplain of a Colorado National Guard unit that fought in the Philippines. In 1903, he became a chaplain in the regular Army. During the Great War, he was chaplain of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment in France. Although cavalry units were not well adapted for the nature of combat in France, the 2nd’s troopers joined three offensives.

After ordination, Charles Wright Freeland ’81 also became an Army chaplain, serving in Iowa, the Philippines, Texas and Virginia. He joined General Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa, and in France he was chaplain of the 6th Cavalry Regiment, largely engaged in hauling artillery and military police duties.

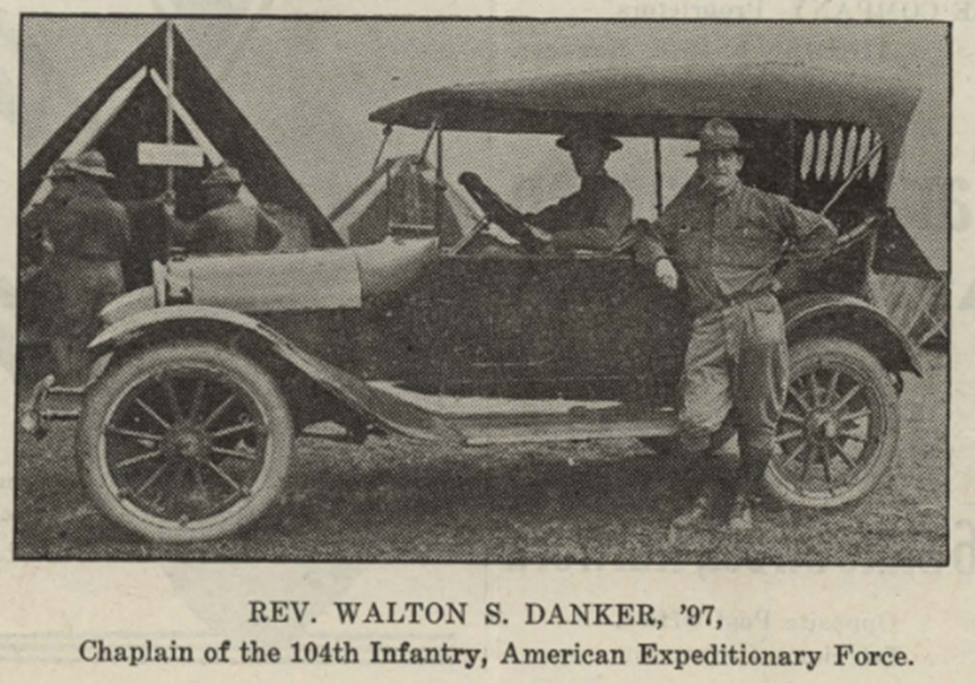

Walton Stoutenburgh Danker ’97 was first a pastor in New Jersey and New York. When he became rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Worcester, he joined the Massachusetts National Guard, and in 1917 he became chaplain of the 104th Infantry Regiment of the 26th “Yankee” Division. He received the Silver Star and the Croix de Guerre for caring for the wounded and dying in the regiment’s fierce engagement at Seicheprey, France, in April of 1918. He was badly wounded by shellfire in June. His brother Frederick, a YMCA worker in France, was with him when he died.

In 1918, Rev. Remsen Brinckerhoff Ogilby, the future President of Trinity, returned to the U.S. from the Philippines and became an Army chaplain, first at West Point. He then served at Debarkation Hospital No. 5 in New York City. Afterwards, he was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Reserve.

While Robert Sanders Hooper ’15 was serving as a chaplain at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, he was felled by the “Spanish flu” and died on Oct. 16, 1918.

After ordination and parish work in Pennsylvania and New York City, Sydney Key Evans ’95 became a Navy chaplain in 1907. In the USS Minnesota, he circled the world with the Great White Fleet. During World War I he was chaplain at the U.S. Naval Academy; his service there was recognized by award of a Special Letter of Commendation with Silver Star. When he retired in 1935, he was the Navy Chief of Chaplains.

Clergy were exempt from conscription, but Rev. Joseph Noyes Barnett ’13 stated, “I want to be one of the soldiers, to eat and sleep and fight with the boys and to be in a position to be of real help when a comrade is in trouble or is disgruntled and needs a smile or a slap on the back.” Sergeant Barnett served in France in the 76th Infantry Division’s 303rd Machine Gun Battalion. After the war, he returned to the ministry, becoming the National Chaplain of the American Legion.

In a tortured time, many Trinity alumni were healers—some of bodies, others of souls.

This article is the seventh part of a series. For part six, click here. For part eight, click here.

+ There are no comments

Add yours