Donald M. Bishop ’67

Alum Contributor

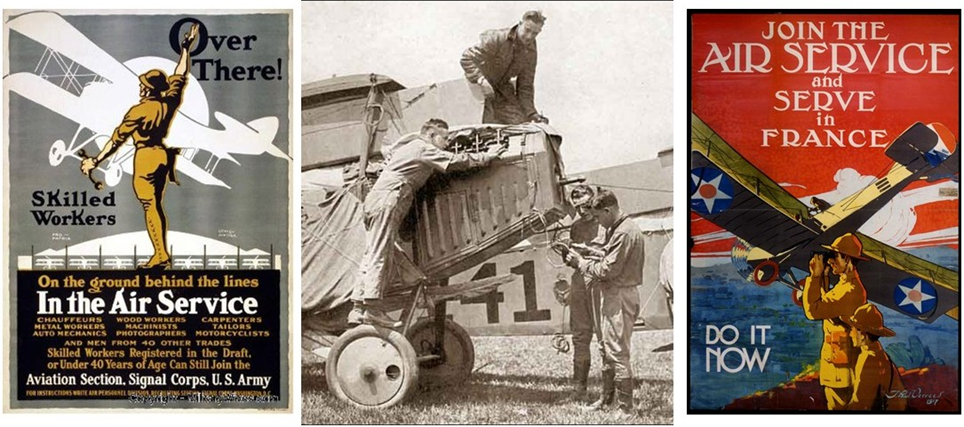

The Wright brothers made their first short flight from Kitty Hawk at the end of 1903. The Great War opened just over a decade later, and aircraft soon began to play roles on the Western Front. The war supercharged innovation and technical advance, and in only four years aircraft became faster, more capable and carried heavier loads on many missions—observation (reconnaissance), bombing, aerial attacks on the trenches and dogfighting between pursuit planes.

In a time of mass slaughter and inconclusive trench warfare, the aviators captured public attention as “aces” and “knights of the air.” “The Red Baron,” “Captain Eddie” Rickenbacker (the top U.S. ace), and the Arizona “Balloon Buster” Frank Luke became household names.

As Trinity alumni and students joined the armed forces, some learned to fly, and some would tangle with the German Fokker or Albatros fighters. Others pioneered bombing of targets behind the German lines, and some became experts in the observation of ground targets from the air. Yet other Trinity men provided the training and maintenance that enabled air power in the First World War—and pointed the way to the future.

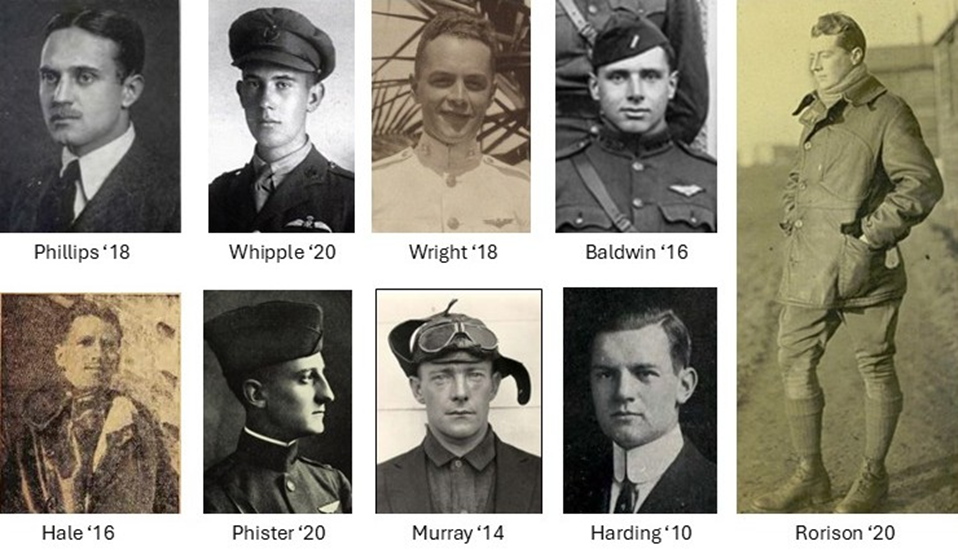

Rufus Colfax Phillips, Jr. entered Trinity with the Class of 1918 but left for the war. He joined the Royal Flying Corps (the predecessor of the Royal Air Force), trained in Canada and flew combat in France. He returned to the College and received his degree in 1919.

Sidney Herman Whipple ’20 became a Flight Lieutenant in the Royal Air Force. As one account reported, “The flight commander dove for the enemy plane, but his gun jammed, and he slid out of the way so that Whipple got his chance. Whipple turned loose his machine gun and says that he saw the pilot of the Hun plane sag in his seat. The plane dropped and then burst into flames.”

After initial flight schooling in Ohio, John Lee Chadbourn Rorison ’20 finished pilot training in England. He was first an American officer assigned to 85 Squadron and then 24 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, both times flying the S.E.5. manufactured by the Royal Aircraft Factory. He was officially credited with two kills of German aircraft. In the final weeks of the war, he was assigned to the 25th Aero Squadron of the U.S. Air Service.

Navy Ensign Arthur Houston Wright ’18 qualified as a naval aviator, but he was transferred to the Marine Corps (its eleventh pilot) and the First Marine Aviation Force. First Lieutenant Wright was cited for bombing “enemy bases, aerodromes, submarine bases, ammunition dumps, railroad junctions, etc.” He flew daring missions across the English Channel. Stricken with influenza, he died twelve days before the armistice; his award of the Navy Cross was posthumous.

Henry L. Watson ’05 (West Point ’07) became a pilot and later commanded the U.S. 9th Aero Squadron. Its unique mission in aircraft painted black was to perform long-range strategic night reconnaissance over the entire length of the U.S. First Army’s sector of the Western Front—detecting from the lights below enemy railroad activity, troop concentrations and the location of antiaircraft searchlights and batteries. Its aircraft was the French Breguet 14B.2 bomber (the first image in this article).

Guy Maynard Baldwin ’16 was a member of the Connecticut National Guard’s Troop B, but he moved to the Air Service, learned to fly in England and joined the 25th Aero Squadron. The pursuit squadron deployed to France, but due to delay after delay, it only flew two patrols the day before the war ended.

Warren L. Hale ’16 and 400 other American aviators, under the command of the future Mayor of New York City, Fiorello LaGuardia, were trained to fly by the Italian Air Force in Foggia, and Hale earned an Italian decoration. The “Foggiani” then joined units of the AEF Air Service in France.

Leaving Trinity to enlist in the summer of 1917, Lipenard Bathe Phister ’20 graduated from the Air Service’s Ground School at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He completed his flying training in France, and he served as a staff-pilot at the Observers’ School at Tours.

James Patrick Murray ’14 entered Trinity with the Class of 1915 but graduated in 1914. He joined the Royal Flying Corps in Toronto in 1917. After winning his wings, he became an instructor pilot.

Clinton Jirah Backus ’19 was commissioned in the Field Artillery in 1918; he trained first in an artillery unit and then as an aerial observer positioned behind the pilot. He reported to the famed 90th Aero Squadron in France in November of 1918, but after the armistice.

At the Airfields

William Hill “Bleeck” Bleecker, Jr. ’12 ran track and played football and hockey at Trinity. During the war he was commissioned in the Army’s Air Service, and he served in France with the 103rd Aero Squadron equipped with French Spad fighters. It was the first U.S. Air Service unit to fly combat in the war. Lieutenant Bleecker was the unit’s supply officer.

As the Army Air Service expanded in France in 1918, skilled aviation maintenance was badly needed. Four maintenance regiments were organized, each with 3500 men recruited from among automobile mechanics. Joseph James Shapiro ’14 became First Sergeant in the 1st Motor Mechanic Regiment. After the war he ran local businesses, and he twice served as Hartford’s police commissioner.

Oscar Wilder Craik ’16 was commissioned in the Army’s Air Service during the war, and he commanded a detachment of motor mechanics in England, working on ignition systems for the new American-designed/made Liberty Engines.

Moses Aaron Berman ’14 was assigned to the 52nd Aero Squadron in Texas, which deployed early to France in 1917 as a construction squadron, the 464th. For a year it moved from airfield to airfield constructing hangars, barracks, warehouses, water towers and power plants. The “stubborn combatant” faced by Sergeant Berman and his fellows was…mud.

And the Balloons

All armies on the Western Front used cable-tethered, hydrogen-filled observation balloons attached to divisions, corps and armies for observation and “reglage,” adjusting artillery fire. Heavier-than-air winged aircraft were the future of military aviation, but during the war lighter-than-air balloons played an important role, so much so that the phrase “when the balloon goes up,” meaning “when the fighting begins,” is still commonly used in today’s U.S. armed forces.

Captain of the tennis team at Trinity, Paul Curtis Harding ’19 enlisted as an ambulance driver, but he was soon commissioned in the Air Service. In April of 1918 he joined the 30th Balloon Company. After training in Waco and Fort Omaha, it shipped out for Europe in October of 1918. The 30th landed in France on Nov. 3 and reached the front the afternoon of Nov. 11.

The Future of Aviation

After the war, Lieutenant Colonel Henry L. Watson remained in the Army; the Air Service Journal called him “one of the most efficient men in the Air Service.” He commanded Chanute Field in Illinois and Mather Field, California—Army Air Service incubators. He led the first flight across the Sierra Nevada mountains, communicating the role of Army aviation to the public.

Rupert Colfax Phillips’s career included aviation, airport planning and management. In the Second World War he taught aviation cadets to fly, and in 1944 he founded the Airways Engineering Corporation.

Karl Hilding Beij ’15, who had been commissioned in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and served in France, published Astronomical Methods in Aerial Navigation in 1924 and received a patent for an aircraft sextant the next year.

After the war, James Patrick Murray was a pioneering U.S. Air Mail pilot, and he became a senior executive with Boeing. His 1972 New York Times obituary noted he was “instrumental in persuading the armed forces not to drop the development of the B‐17 Flying Fortress after initial test trouble. The B‐17 went on to be a mainstay of American bombing tactics during World War II.”

Trinity alumni took part in the “war in the air” over Europe. And many who served in this infancy of military aviation went on to play roles in what would become an aviation century.

This article is the ninth part of a series. For part eight, click here. For part 10, click here.

[…] part of an ongoing series, with new installments releasing on Sundays. For part ten, click here. Part 12 will be released Jan. 26, […]