Iqra Athar ’26

News Editor

On Sept. 18, 2024, the Trinity Tripod interviewed Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Matthew Hyde about the admissions landscape at Trinity College following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to end affirmative action in college admissions. The ruling is part of the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard/UNC case that has forced institutions nationwide to reevaluate their admission strategies for maintaining diversity without racial categorization or quotas.

During the interview, Hyde shared how Trinity has adapted by shifting toward holistic reviews and approaches to understand a candidate’s background. “The enormity of a young person can’t fit into the confines of a common application,” Hyde explained. He elaborated on the college’s efforts to assess the “merit beyond academics” of each applicant, focusing on how they engage with the world and their potential to contribute to a dynamic campus environment.

Despite the ruling, Trinity remains committed to fostering a diverse educational community. “We’ve consistently evaluated academic merit. Beyond that, we now delve deeper into how students from historically underrepresented backgrounds might enrich our community,” Hyde remarked. The college introduced an optional essay prompt for students to discuss the identities they claim and the challenges they face, providing new avenues to understand applicants’ unique experiences and perspectives. Hyde emphasized that this move was designed to adapt to Justice Roberts’ allowance for considering the “experience of race” rather than race itself.

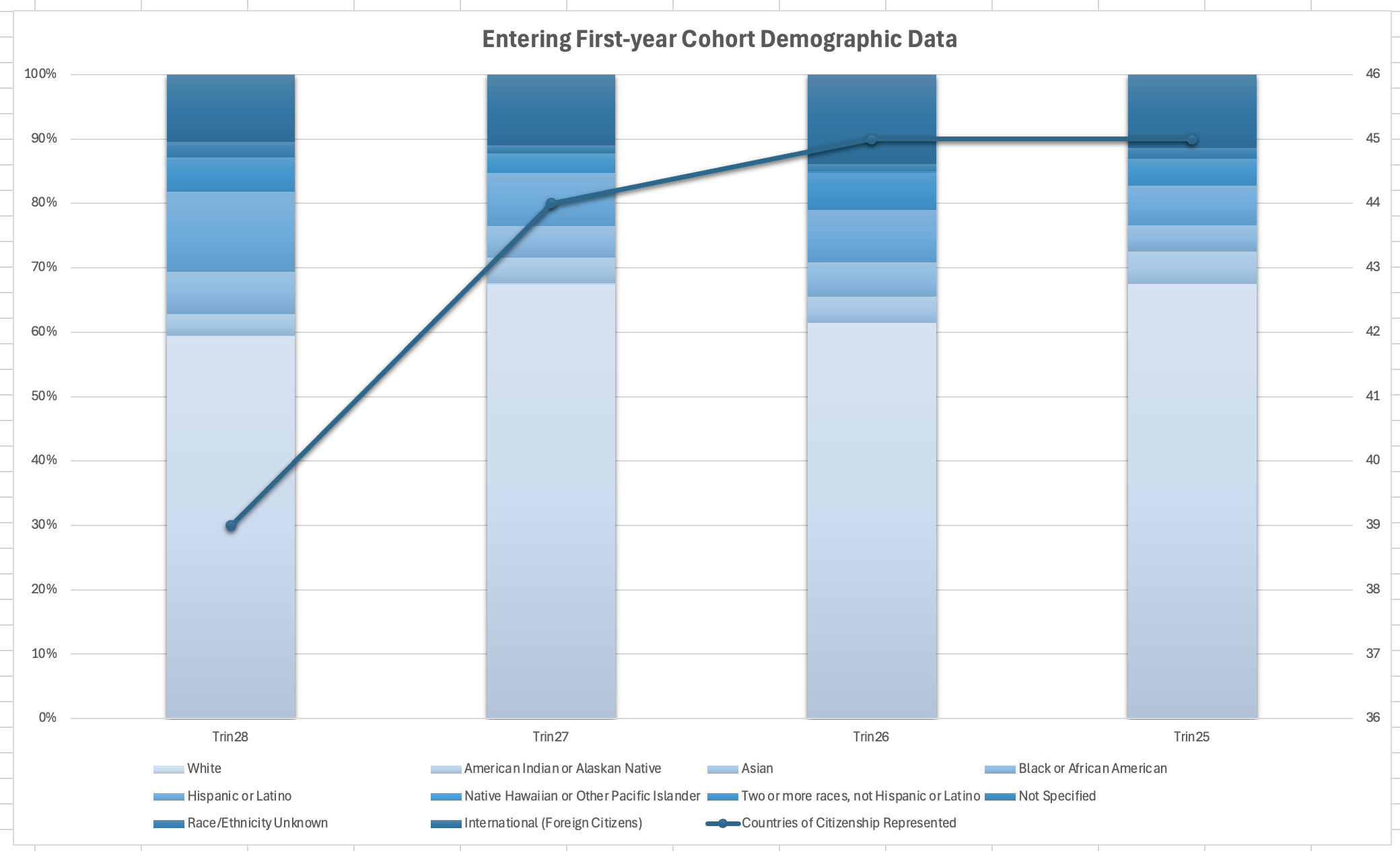

In the data shared by Hyde (see figure), the Class of 2028 shows an increase in domestic students of color, rising from 23% last year to 31% this year. Notably, the Hispanic or Latino student population nearly doubled from 6.9% to 13.9% and Black or African American representation grew from 4.6% to 7.3%. Conversely, Asian student representation declined from 5.6% to 3.7% and White students decreased from 76.2% in the Class of 2025 to 66.2% in the Class of 2028, reflecting ongoing efforts to diversify future classes.

Additionally, the international student population which was a point of scrutiny last year due to perceived reductions has been intentionally adjusted. “We’ve dialed back our offers internationally… not dramatically, but intentionally,” Hyde explained. The Class of 2028 has international students making up roughly 11.7% of the body, a decrease from 12.3% in the Class of 2027 and 16.1% in the Class of 2026, which had the largest proportion of international students in Trinity’s recent history. This adjustment aligns with the goal of balancing resource investment, with Hyde noting, “International students are an absolute priority for us, but we strive to find a balance that allows us to be sustainable in our approach to investing our finite resources of financial aid.”

Addressing the transparency of these demographic insights, Hyde emphasized the college’s ongoing commitment to clear and open reporting. “We share the backdrop and demographics of our class at matriculation, and then with our communications office in terms of how the class has come together and the diversity in that class,” he said. This data is finalized at the census date at the end of September each year, ensuring accurate reporting. Hyde also detailed the enhanced financial aid strategies aimed at reducing dependency on loans and making Trinity more accessible across economic backgrounds.

Comparatively, other institutions have reported mixed outcomes in their diversity metrics this year following the Supreme Court’s decision. Yale University, for example, maintained stable enrollment figures for Black and Latinx students with 14% African American and 19% Hispanic or Latino in their Class of 2028. In contrast, institutions such as MIT and Amherst College experienced declines. MIT saw Black student numbers fall from 15% to 5% and Hispanic or Latino students decrease from 16% to 11%. Amherst reported a drop in Black students from 11% to 3% and Hispanic students from 14% to 10%.

Athar notes that Dean Hyde believes that Justice Roberts allowed for the consideration of the “experience of race” in college admissions rather than race itself, and therefore offers an optional essay in the admissions application. But apparently Athar has not looked into the final Supreme Court decision, in which Justice Roberts writes that “universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.” That would be a good detail to add, right?

Athar writes about Trinity’s “clear and open reporting” of racial statistics – down to a tenth of a percentage point! – but provides zero insights about how the data collection is done post-affirmative action. How does Hyde have data which can be shared at matriculation (typically in August) when some kind of unexplained census is apparently finalized afterwards in September?

And what is this census, anyway? The article offers no details on what it entails nor how it’s compliant in a post-affirmative action world. Does Trinity make a “best guess” about someone’s race from the admissions application – and its carefully crafted “experience of race” essay option to try to get around the Court’s decision – and then run a survey (voluntary or not) afterwards to make sure the admissions team “got it right?”

If not, how does Hyde know – to a tenth of a percentage point – the racial makeup of a class when that information is now illegal to add to an admissions application? Does he walk around campus checking people’s faces, skin colors and names?

Trinity may or may not have “clear and open reporting” in this arena, but this article sure didn’t explain much about how this data is collected.

Colleges still collect and report racial data. From the DoJ’s FAQ on the end of AA, “In collecting and using data, institutions should ensure that the racial demographics of the

applicant pool do not influence admissions decisions… The Court’s decision does not

prohibit institutions from reviewing such data for other purposes, but institutions should consider

steps that would prevent admissions officers who review student applications from using the data

to make admissions decisions based on individual applicants’ self-identified race or ethnicity.”

You are correct that SFFA banned racial discrimination in college admissions, but it also explicitly provided for the type of essay described in the article. Roberts writes, “A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination. Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university.”

Thanks for the helpful comments. They were clarifying – especially on the data collection front.

The fact remains that Justice Roberts also warned against the use of essays as a surreptitious means of propping up affirmative action: “ Universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”

At the same time, you rightly point out that Roberts did identify opportunities for applicants to provide a holistic view of applicants, which can include race.

Trinity’s embrace of a discrete application essay on race seems to really ride the line. Then again, Roberts seems to have spoken out of both sides of his mouth. It’ll be interesting to see how legal scholars interpret the nebulousness of parts of this ruling in the years to come.