Jack P. Carroll ’24

Contributing Writer

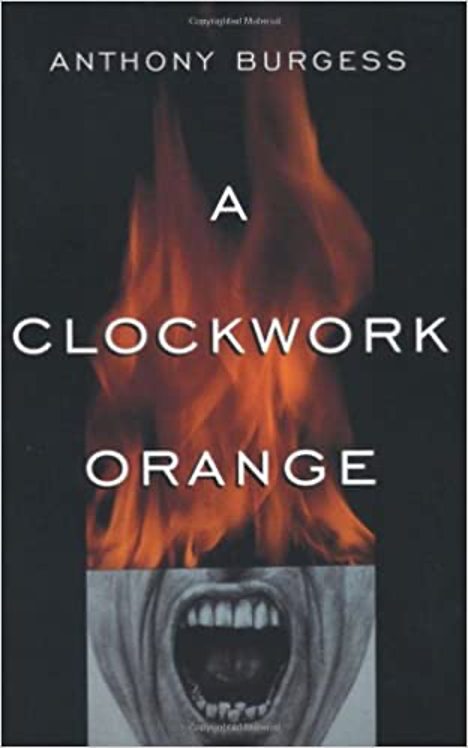

I believe that every college student in the U.S. should be required to read the all-too relatable Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange, as the social and emotional struggles of Alex are emblematic of the developmental trials that many young people face as they transition from their teenage to young adult years. Furthermore, by observing Alex and his development from a pleasure-seeking criminal to a conscious young man who seeks for order and stability in his life, I believe that many young readers will be able to see themselves in Alex, and in turn, become more sympathetic to others in a similar position.

As my peers and I begin our college experience, it is deeply important for us to remain considerate to others as we all are trying to develop our futures and find our ultimate place in the world as flawed and imperfect beings.

For those who have not yet read the novel, the plot of the storyline is as follows: Alex, the Nadsat speaking anti-hero, is a fifteen-year-old criminal who, along with his gang members, spends his nights marauding the dystopian city in which he inhabits. His criminal pursuits come to an abrupt end when he is arrested. Later, Alex is forced to endure a government-sponsored rehabilitative process called “Ludovico Technique,” also known as aversion therapy, in which members of the ruling class attempt to rid him of his violent impulses. Nevertheless, Alex’s malevolence subsides only temporarily, and after being saved by a group of revolutionaries who are highly critical of the government, he plans for another night out on the streets–that is until he runs into his friend and former gang member, Pete, who at the end of the novel is a responsible and married man that Alex comes to appreciate.

In a wretched state of self-reflection, in which he shames himself for his vile behavior as a teenager, Alex makes one of the most simple yet resoundingly accurate analogies to depict the turbulent nature of growing up:

Youth is only being in a way like it might be an animal. No, it is not just like being an animal so much as being like on of these malenky toys you viddy being sold in the streets, like chellovecks made out of tin and with a little spring inside and then a winding handle on the outside and you wind it up grr grr grr and off it itties, like walking, O my brothers. But it itties in a straight line and bangs straight into things bang bang and it cannot help what it is doing. Being young is like being one of these malenky machines.

Indeed, Burgess is correct in his depiction of the individual’s younger years as clueless, mistake ridden, and at times painful, as summed up by the term “bang.” As I am still a young person myself, I could not think of a more appropriate way to describe adolescence. In a time in our lives when most of us have very little responsibility outside of school, sports, and our friend groups, it is nearly impossible to overcome the myopic foresight that characterizes our youth. It is for this reason that mistakes stemming from immaturity, selfishness, and a vague sense of responsibility are bound to be made.

Nevertheless, some people may remain buoyant and high-nosed on their throne of self-righteousness and remark ignorant statements such as, “Don’t make mistakes” and dismiss the reality that children and teenagers, like Alex, make mistakes when acting in accordance with their own immediate interests, in part, due to their limited life experience and inability to play out the multidimensional consequences of their actions.

However, to these societal nobles and descendants of Abel, I would further respond to them with the comments of clinical psychologist and professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, formerly at Harvard University, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson. In a live panel discussion in which he highlights the confined and undeveloped nature of the human experience in adolescence, he argues:

…I tell eighteen year olds: Six years ago you were twelve! What the hell do you know? You’re under the care of the family or the state; you haven’t established an independent existence; You haven’t had children; You haven’t started a business; You haven’t taken responsibility for anything; You don’t have a degree; You haven’t finished your courses; You don’t know how to read; You can’t think; You can’t speak; You’re ill-kempt; You don’t know how to present yourself…

Bang.

As much as a slap-in-the-face as these comments are, they are, nevertheless, true. As my peers and I enter into college, I think it is imperative for us to remain unified, in part, by the humility and inexperience of our current condition. As bright, hard working, talented, and intellectually-driven that any of us may be, or at least perceive ourselves to be, we still have a long road ahead of us for individual development and self-improvement.

In fact, this was once pointed out in a live talk by a television host and comedian who I think we can all appreciate, Conan O’Brien. When reflecting on his college years at Harvard University, he presents individual development as an ongoing process that we follow for our entire lives:

I used to think that if I could look at someone like myself, I thought that they had figured it all out and they were fine. And wouldn’t it be magical if I could be…If I could have my own show and be funny and everyone knew who I was and most people liked it. That would be a great thing and that would solve all my problems. I would like my future self to say that’s not the case, it’s actually day-by-day, how you do your work, how you conduct yourself, how you treat people, the joy you get out of your work. That is far more important.

He later notes:

You just have to be willing to screw up and not freak out when you do screw up, because you will screw up.

To my peers, as we enter college let us keep in mind the theme of trial and error that, as Burgess reminds us, characterizes the inexperience of our adolescence, as well as the Alexian comments of the previously quoted figures. As symbolized by the cover of A Clockwork Orange, which displays a man’s face on fire (the flames symbolizing transformation), we are in a continuous state of development, so let us make persistent efforts to remain sympathetic to our current flaws and previous mistakes and establish a community that is aimed at attaining peace and understanding.

All of us will soon be very busy individuals, so let us not waste our time on the immaturities of scandal, cancel culture (which former President Barack Obama has spoken outwardly against), and any effort to bring others down in malice and resentment.

Though such efforts may be difficult as they require us to defy our impulses and immediate emotions, we should, nevertheless, do everything in our power to develop a welcoming, forgiving, and understanding community.

As was once brilliantly stated by the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke, one of the few members of the British Parliament who opposed engaging in war on the rebelling colonies during the American Revolutionary War: Our patience will achieve more than our force.

+ There are no comments

Add yours